By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

THE SUBLIME COURAGE OF A FRONTIER BOY

John Warren Hunter, in 1910

FROM Hunter’s Frontier Times Magazine, January, 1948

Captain Cal Putman came to Texas in 1821, and with his family settled on the San Gabriel, in what is now Williamson county, and built the first house — a block house — erected in that territory, and not far from where Liberty Hill now stands. This was long before Austin was founded, and his nearest white neighbors were the Hornsbys, who had formed a settlement at Hornsby's Bend, on the Colorado. Indians often paid friendly visits at the block house, and were always shown kind treatment, and they seldom abused the favors shown them.

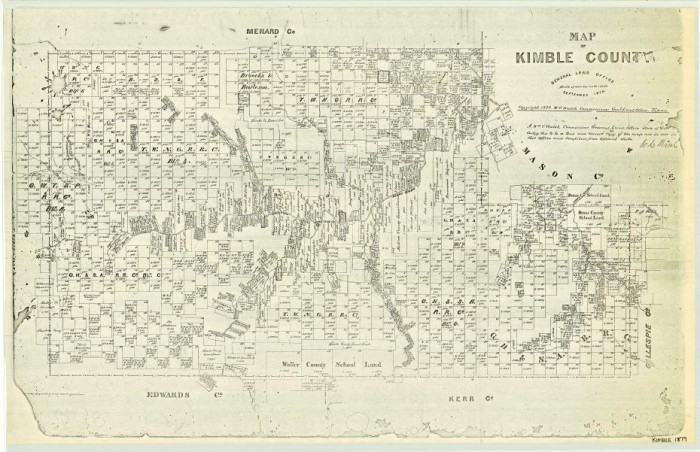

Early in the 1850s Mr. Putman moved to Llano county and settled on Hickory Creek, near House Mountain, where in the course of time he established a comfortable home. He and his good wife raised a large family, four sons and several daughters. In the fall of 1864, Captain Putman, accompanied by his son, Harve, started on a hunting expedition on the upper Llano river, in the territory now included in Kimble county. In those days game was abundant in this region, and large numbers of wild cattle roamed at will over the vast range. Most of the cattle were unbranded and were subject to the claims of any huntsman who chanced to come up with them on the range. This was the kind of game Mr. Putman was seeking, his aim being to lay in a sufficient supply of beef on this trip to supply the wants of his family for the winter.

Their outfit consisted of a small carryall wagon, without cover, in which was stored bedding, provisions, and several sacks of corn on the ear. The wagon was drawn by two horses, while an extra horse was led at the rear end of the vehicle. Their armament consisted of a double barrel shotgun and an old army rifle with about a half dozen rounds of ammunition, but this latter they expected to replenish when they reached Fort Mason, as they had to pass through that post on their way to their chosen hunting grounds. The United States troops had abandoned Fort Mason at the beginning of the war, and at the time in which I write, only a small company of rangers held the place for the protection of the few scattering ranchmen and their families, who lived on that part of the extreme border.

Great was Putman's disappointment when he reached Mason, to find that not a cartridge nor an ounce of powder could be had in the place. Taking an inventory of his stock, he found that he had six rounds of ammunition, two cartridges for his army gun, and four charges of shot, powder and caps for his shotgun. Being a dead shot with either gun, he reasoned that out of the six charges he could safely count on at least four fat beeves, and the flesh of these, when cured, would more than load his wagon. As to Indians, he apprehended no danger whatever. It had been a long while since they had raided that particular section. He knew the metal of his son, then about 14 years old, and an excellent shot and if perchance the Indians attacked them, the twain could run a bluff even with empty guns and stand them off. These reflections hastened his decision and they left Mason and headed for the Saline country, up on the Llano, aiming to reach the Saline creek that evening.

When they reached the Leon creek, about 20 miles west of Mason, they discovered a body of horsemen, which at first they took to be a squad of ranger or ranchmen, but on closer scrutiny the keen eye of Harve detected the Indian garb. The horsemen were at quite a distance when first seen, but were now approaching at a rapid gait. Seeing this, Putman drove into a grove of scattering postoak trees nearby and prepared for action by tying his horses securely to two trees, near which he had stopped his wagon, and by the time this was accomplished, the Indians, with loud yells, were upon them. There were thirteen of the red savages, and they made a furious charge. Being an old frontiersman, Mr. Putman knew that the sight of a gun in the hands of a white man when at bay became an object of dread and terror to the average Comanche, and acting on this knowledge, he told Harve to reserve his ammunition and not to fire until he gave the word, but to put on a bold front and to present his gun as if in the act of shooting every time an Indian got too close. This plan was carried out successfully in this first charge of the Indians, who fell back at a safe distance, dismounted and again advanced on the beleaguered, this time on foot. From the cover of trees they opened fire on the Putmans with a few guns which they had along, and this was kept up until it seemed they had exhausted their ammunition, when they advanced nearer and began to shoot arrows. Up to this time neither of the Putmans had fired a shot. Only yells of defiance from that wagon, coupled with invitations for the redskins to come a little nearer. Showers of arrows fell around them. Harve wore a white wool hat, a new one and the boy was very proud of his headgear. A new hat was a rarity, especially for a boy, in those days. An arrow pierced it and pinned it to a tree against which he was standing. This made him mad and he begged his father to let him shoot the Indian that sent that arrow through his new hat. The father told him to hold his ammunition and not to fire until he so ordered. However, this did not satisfy him; he was bent on getting even, and abandoning his tree, he gathered up and broke every arrow that fell within his reach, thus rendering them useless in case the Indians should prevail, which, just then, seemed highly probable. While thus engaged, his clothes were pierced in different places by arrows, and his father failed to give him the word "fire."

This failure of the Putmans to use their guns served to embolden the Indians, and gradually they came nearer. At close range the Indians fired a shot from a gun, the leaden missile passing through Captain Putman's thigh, rupturing one of the small arteries. About the same moment a shot struck Harve's foot, tearing away his shoe and leaving his big toe hanging by a mere shred. This was about 4 o'clock in the evening and the Indians became more bold when they saw the effects of their own shots, and yet when the white man's guns remained silent, an Indian, more daring than the rest, advanced to the wagon and fired on Harve at a range so close that the blaze of the gun set his clothes on fire. This was getting too close for the Captain, and although desperately wounded, he raised up his old shotgun and landed 8 buckshot into the carcass of the old copper colored savage. Almost at the same instant Harve drew a bead on another — the one who had shot up his new hat — and with a ball from his old army gun, sent him to the happy hunting grounds. Both of these Indians fell near the wagon and were speedily carried away by their comrades, who made a charge in full force in order to recover the bodies.

_____________________________________

_____________________________________

The Indian killed by Captain Putman seemed to be the leader or chief of the band, and after his fall his followers seemed more determined than ever to have the horses and scalps of the Putmans. The charges were more frequent but not so close. Towards sundown, Captain Putman became so weakened from loss of blood that he fainted. Everything now depended on the bravery of the son, who, when the Indians made a charge, presented that terror inspiring gun, causing them to fall back. Realizing his father's condition, Harve took the water keg from the wagon and poured some of the contents in the Captain's face, which served to revive him.

When darkness came on the Indians withdrew to the channel of a small dry creek or branch about 300 yards distant, built a fire and seemed to be waiting for the rising of the moon, which came up about ten o'clock. At dark Captain Putman regained consciousness but was too weak to raise himself from the ground. What must be done? Being a large man, weighing over 200 pounds Harve found it impossible to lift him into the wagon, although he made several fruitless efforts.

Finally the father told him to leave him, mount on of the horses and go to Gamel's ranch, some five miles distant, and get help. Before leaving, Harve succeeded in getting his father in a sitting posture with his back against a tree. He next tore apart the box, or bed, of the frail wagon and with this material and the sacks of corn, he built a rude barricade about his father, and placing the loaded double barrel shotgun by his side, told him to shoot at the first object that came near his fort. He insisted on leaving the army gun also, contending that his father would, in all likelihood, stand in greater need of it, but to this the parent would not consent.

In one of the charges, an Indian had thrown a handsomely mounted tomahawk at Harve. This he secured and before leaving, placed it by the side of his father, knowing full well that in close quarters the brave old pioneer would put it to proper use.

When these hasty preparations were made, Harve bade his father be of good cheer, that he would soon return with help if help was to be had, and if no aid could be procured at the ranch, he would return alone and fight it out to a finish with the cowardly redskins. Mounting the best horse of the three, Harve quietly stole away in the darkness. His father had pointed out the direction in which the ranch lay and in less than an hour he had reached Mr. Gamel's and told his story. Tom Gamel and Jesper Chapman were soon in the saddle and the three hastened to the side of the wounded pioneer. The moon was rising when they reached the fortification where they found the Captain in the same position in which his son had left him, but his strength was so far gone that he scarce was able to speak above a whisper. The Indians were yet around their camp fire, and Harve insisted that he and the two men with him take chances on killing a few more of them. His father was desperately, probably fatally wounded, while he himself was suffering intensely from the loss of a toe and he thirsted for revenge. But wise council prevailed. Mr. Gamel told him that their only course was to act on the defensive. The enemy was too many for them and the best thing to do was to get the wagon bed together, hitch up, and get the wounded father to the ranch as soon as possible, and if the Indians made an attack, they would stay closely together and kill as many as they could.

It was after sunrise the next morning when they reached the Gamel ranch, where the Captain received the tenderest care. It was several weeks before he was able to return home, and his recovery was only partial. He never fully recovered from the effects of the wound he received in that fight, although he lived to a ripe old age. He died at his home near House Mountain some time during the year 1880.

Harve's wound healed, or to use his own expression, "the toe grew out again," but he never forgot the scratch the Indians gave him that day on the Leon, as was proven on many subsequent occasions.

20,000+ more pages of Texas history, written by those who lived it! Searchable flash drive or DVD here

$129.95 $89.95

Option 2

Get 352 issues packed with stories like the one you just read

$99.95 $69.95

*********

Prefer to read hard copy magazines?

Click here to get your 6 hard copy FRONTIER TIMES MAGAZINES

‹ Back

Comments