By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

THE HORRIFIC SCALPING OF JOSIAH WILBARGER

[From J. Marvin Hunter's Frontier Times Magazine, February, 1950]

Many incidents in Texas history illustrate the verity of the saying that, "Truth is stranger than fiction," but none perhaps, so forcibly as the circumstances of the scalping of Wilbarger—since their dramatic interest includes an occurrence as remarkable, if indeed not as mysterious, as any to be found within the range of spiritualistic and psychological literature.

Among the sturdy emigrants to Austin's colony, was Josiah Wilbarger, a native of Bourbon county, Kentucky, who came with his young bride and his father-in-law, Leman Baker, from Lincoln county, Missouri in 1828.

In March, 1830, after a couple of years spent in what is now Matagorda and Colorado counties, Wilbarger located his headright league ten miles above Bastrop on the Colorado, and with his wife, and baby, and two or three transient young men, removed to that then extreme and greatly exposed section, and erected his cabin. Here, for a time, he was the outside settler, but soon other fearless pioneers located along the river, some below, others above—the elder Reuben Hornsby becoming, and for several years remaining, the outside sentinel of American civilization in that direction."Mr. Wilbarger," says Brown, "located various lands for other parties in that section, it being Austin's second grant above the old San Antonio and Nacogdoches road, which crossed at Bastrop."

Early in August,1833, Wilbarger, in company with Christian, a surveyor, and three young men, Strother, Standifer and Hanie, rode out from Hornsby's to look at the country and locate lands. On reaching a point near Walnut Creek, some five or six miles northwest of where the present capital city now stands, they discovered an Indian on a neighboring ridge, watching their movements. He was hailed with signs of friendship, but as the party approached, the Indian rode away, pointing toward a smoke rising from a cedar break to the west. After a short pursuit, fearing they were being decoyed into a large camp of hostile Indians, the whites halted, held a short consultation, and at once determined to return to Hornsby's. On Pecan Spring branch, some four miles east of the present city of Austin, and in sight of the present dirt road leading from Austin to Manor, they stopped to refresh themselves and horses. "Wilbarger, Christian and Strother unsaddled and hobbled their horses, but Hanie and Standifer left their animals saddled and staked them to graze." While the men were eating they were suddenly charged upon by about sixty savages, who had quietly stolen up afoot under cover of the brush and timber, leaving their horses in the rear, and out of sight. The trees near them were small and afforded but little protection. However, each man sprang behind one and promptly returned the fire. Strother had been mortally wounded at the first fire, and now Christian was struck with a ball, breaking his thigh bone. Wilbarger sprang to the side of Christian, set him up against his tree, primed his loaded gun, and jumped again behind his own tree—receiving in the operation a flesh wound in the thigh and an arrow through the calf of his leg; and scarcely had here gained the protection of his tree, when his other leg was pierced with an arrow. Meantime, the steady fire and deadly aim of the whites had telling effect, causing the Indians to withdraw some distance and out of range. Up to this time Hanie and Standifer had bravely helped to sustain the unequal contest, but now, seeing that Strother was dying, Christian perhaps mortally, and Wilbarger badly wounded, they took advantage of the opportunity to secure and mount their horses. Wilbarger, seeing himself thus deserted, and his horse having broken away and fled, implored the two men to stay with him and fight; but if they would not, nor allow him to mount behind one of them. Just then, however, seeing the enemy again approaching, they fled at full speed, leaving Wilbarger to his fate. "The Indians," says Brown, "one having mounted Christian’s horse, encircled him on all sides. He had seized the guns of the fallen men,and just as he was taking deliberate aim at the mounted warrior, a ball entered his neck, paralyzing him, so that he fell to the ground and was at the mercy of the wretches.

With exultant yells the Indians now rushed upon, and stripped him naked, and passing a knife entirely around his head, tore off the scalp. Though helpless and apparently dead, the poor man was fully conscious of all that transpired, and afterwards, in recounting the thrilling experience, said that while no pain was perceptible, the removing of his scalp sounded like the ominous roar and peal of distant thunder. The three men were stripped, Christian and Strother scalped and their throats cut, and all left for dead; after which the savages retired.

Wilbarger lay in a dreamy, semiconscious condition till late in the evening, when the loss of blood finally aroused him. Crazed with the pains of his numerous wounds, and consumed by an intolerable thirst, he put forth the little remaining vitality in an endeavor to reach the spring nearby, which he at last accomplished, dragging himself into the water, where he lay for some time, till chilled and quite numb, he crawled out on dry ground and fell asleep. When he awoke he found the flow of blood from his wounds had ceased, but horrors! exposed in the hot sun, the detestable "blow flies" had infested and literally covered his scalp and other wounds. Again slaking his thirst from the limpid little stream and partially appeasing his hunger with a few snails he chanced to find, he felt refreshed, and as night approached, determined to travel as far as he could in the direction of Hornsby's. But poor man, he did not realize his enfeebled condition from pain and loss of blood. After many efforts he arose and staggered along for perhaps a quarter of a mile, when he sank to the earth thoroughly exhausted, and almost lifeless, at the foot of a large post oak tree, and here, naked, and exposed to the chilling night air, he lay, suffering intensely from cold, and unable to move, till revived by the warm sunshine of the following day.

On arriving at Hornsby's, the two men, Standifer and Hanie, told how the Indians had attacked and killed all three of their companions; and how they narrowly escaped. A messenger was at once dispatched to warn the settlers below, and also for aid, which however, could not be expected before the following day.

And now we will relate a most marvelous coincidence of circumstances—incidents at once so mysterious as to incite credulity of belief, were it not for the high character and known veracity of those, who to their dying day, vouched for their truth:

During the night—that long and agonizing night—as Wilbarger lay under the old oak tree, in a state of semi-consciousness, visions flitting through his mind bordering on the marvelous and supernatural, he distinctly saw standing before him, the spirit of his sister, Mrs. Margaret Clifton, who had died the day before in Florissant, St. Louis county, Missouri. Speaking gently, she said: "Brother Josiah, you are too weak to go on alone! Remain here and friends will come to aid you before the setting of another sun," and then moved off in the direction of the settlement, Wilbarger piteously calling, "Margaret! Stay with me." But the apparition vanished.

That night, about the same hour—midnight—Mrs. Hornsby awoke from a most vivid and startling dream, in which she beheld Wilbarger, alive, scalped, bleeding and naked, at the foot of a tree. Her husband assuring her that dreams were always unreal; and the utter impossibility of this one being true, she again slumbered—till about three o'clock, when she again awoke, intensely excited, and arose saying,"I saw him again! Wilbarger is not dead! Go to the poor man at once;" and so confident was Mrs. Hornsby, she refused to retire again, but busied herself preparing an early breakfast, that there might be no delay in starting to Wilbarger's relief. As the nearest neighbors arrived in the morning, Mrs. Hornsby repeated to them her dual vision and urged them in a most serious manner, to go to Wilbarger in all haste. The relief party consisted of Reuben Hornsby, Joseph Rogers, John Walters, Webber, and others. After quite a search from the vague directions of the two excited men who had escaped from the scene, they finally found the bodies of Christian and Strother; and presently discovered a most ghastly object—a mass of blood—causing them to hesitate and clutch their guns; whereupon the overjoyed man arose, beckoned, and finally managed to say, "Don't shoot, friends; it's Wilbarger, come on." As they approached he sank down and called out, "Water! water!" and when revived, spoke of his sister who had visited him during the night and so kindly had gone for help which he knew would come— firmly believing he had seen and conversed with her in reality. With the sheets provided by Mrs. Hornsby for the purpose, the bodies of Strother and Christian were wrapped and left till the following day, when the party again went out and buried them. In another sheet Wilbarger was wrapped and placed on a horse in front of Mr. Hornsby, who, placing his arms around him, sustained him in the saddle and bore him to the hospitable home and tender care of Mrs. Hornsby, that saintly mother and ministering angel of the frontier. His scalp wound was dressed in bear's oil, and after a few days of tender nursing, the great loss of blood preventing febrile tendencies, he was sufficiently recovered to be placed on a sled and conveyed to his own cabin.

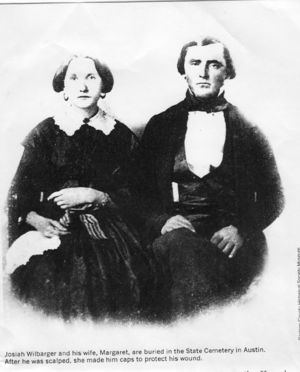

Rapidly Wilbarger recovered his usual health, and lived for eleven years, prospering, and accumulating a handsome estate. But his skull, bereft of the inner membrane and so long exposed to the sun, never entirely covered over, necessitating artificial covering, and eventually caused his death, hastened, as his physician, Dr. Anderson thought, by accidentally striking his head against the upper portion of a low door frame of his ginhouse, causing the bone to exfoliate, exposing the brain and producing delirium. He died at his home in 1845, survived by his wife and five children. His widow, who afterward married Tolbert Chambers, was the second time bereft, and died a widow in Bastrop in 1896. The eldest son, John Wilbarger, a most gallant ranger under Col. "Rip" Ford, was killed by Indians in the Nueces river country, in 1847. Harvey Wilbarger, another son, lived to raise a large family. One married daughter lived at Georgetown, and another at Belton, Texas. Of the brothers and sisters of Josiah Wilbarger, who came to Texas in 1837, J. W. Wilbarger, (author of "Indian Depredations in Texas") died near Round Rock in 1890, and "Aunt Sallie" Wilbarger, long resided at Georgetown, where she died many years since. Another sister who became the wife of Col. W. C. Dalrymple, died many years ago, and still another—Mrs. Lewis Jones—died on the way to Texas. Matthias, a brother, was a noted surveyor, and died of smallpox at Georgetown in 1853.

William Hornsby died in 1901, near Austin, and his parents many years before. The beautiful home and fertile Hornsby farm is still owned by surviving members of the family.

So far as we can ascertain, this was the first blood shed in that part of the state (in what is now Travis county), at the hands of the implacable savages, but it was "the beginning, however," says J. W. Wilbarger, "of a bloody era which was soon to dawn upon the people of the Colorado."

"The vision," continues Wilbarger, "which impressed Mrs. Hornsby, was spoken of far and wide through the colony fifty years ago; her earnest manner and perfect confidence that Wilbarger was alive, in connection with her vision and its realization, made a profound impression on the men present, who spoke of it everywhere. There were no telegraphs in those days, and no means of knowing that Margaret, the sister, had died seven hundred miles away, on the day before her brother was wounded. The story of her apparition, related before he knew that she was dead—her going in the direction of Hornsby's and Mrs.Hornsby's vision, recurring after slumber presents a mystery that made then a deep impression and created a feeling of awe, which after the lapse of half a century, it still inspires. No man who knew them ever questioned the veracity of either Wilbarger or the Hornsby's, and Mrs.Hornsby was loved and revered by all who knew her."

We leave to those more versed in the occult the task of explaining this mystery. Surely such things are not accidents; they tell us of a spirit world and of a God who “moves in a mysterious way, His wonders to perform."

Other incidents of border warfare occurring that year are of minor importance and without exact date or details; at the murder of Alexander, a trapper, near the Ledbetter La Grange road on a small streamlet since called Alexander's Branch in Fayette county; and the killing of one Earthman on Lone Prairie, near the present post office hamlet of Nechanitz in the same county; the adventures of Tom Alley while out hunting horses in the Cummings' Creek community—unexpectedly riding into a camp of Indians, who fired upon and severely wounded him, as he put spurs to his steed and fled. Settlers followed these Indians towards the head of Cummings' Creek, where the trail was lost in consequence of the grass being burned to elude further pursuit.

In the spring of that year a band of Keechi Indians raided the Cummings' Creek settlements in Fayette county, committing various depredations. Hastily collecting a company of twenty settlers, Captain John York pursued, attacked and killed eight or ten of them, dispersing the others. This was, so far as known, their last, and perhaps only real hostile demonstration against the settlers. The Keechis were comparatively a small, insignificant band, of beggarly and thieving propensities, and early lost their tribal existence, affiliating with other tribes.

_____________________________________

_____________________________________

During the same year a traveler named Reed, stopped at Tenoxtitlan Falls of the Brazos, now in the lower part of Falls county. At that time a small party of friendly Tonkawa Indians were camped nearby, and with one of whom Reed "swapped horses, and it is said, drove a shrewd bargain, which he refused to rue. A few days later as the stranger left the vicinity on his return to the United States, he was waylaid and murdered by the exasperated Tonkawas, who appropriated his horse and equipments and fled. The old Caddo chief, Canoma, who was about the settlements a good deal, and then at the "Falls," with some of his warriors, went in pursuit and on the eighth day, returned with seven "Tonk" scalps, Reed's horse and other trophies—receiving a substantial commendation of the settiers."

“Other matters of interest," says John Henry Brown, "occurred in about 1833. The colony of De Leon had increased considerably by the incoming of a good class of Mexicans and quite a number of Americans, including several Irishmen and their families from the United States, the younger members being natives of that country, and among whom were the following: John McHenry (a settler since 1826), John Linn, and his sons, John J., Charles, Henry and Edward, and two daughters, (subsequently the wives of Maj. James Kerr and James A. Moody), who came in 1830-31; Mrs.Margaret Bobo, afterwards Wright, (who came in 1925), Joseph Ware and others. From about 1829 to 1833-34, the colonists of Power and Howitson, with headquarters at Mission Refugio, and McMullen and McGloin, of which San Patricio was the capital, received valuable additions in a worthy, sober, industrious class of people, chiefly from Ireland, a few of Irish extraction, born in the United States, and others who were Amercians. They were more exposed to Mexican oppression than the colonists farther east and equally so to the hostile Indians."

Glancing at the history of colonial Texas about this period, one can but wonder at the signs of substantial and permanent growth, despite all restrictions and obstacles. The spirit of colonization was abroad, and fearless emigrants were constantly arriving overland by the various highways—menaced though they were by lurking savages, who often lay in ambush to pounce upon the new-corners. "In 1833," says Pease, "the tide of emigrants from the United States, which had been interrupted during the administration of Bustamente, began again to flow into the country."

"The history of frontier expansion in the United States" says Thrall, "shows that is no easy task. In Texas the difficulties were very great. It was remote from other settlements—in a foreign country, with a government and institutions entirely different from those of the North; and the country was preoccupied by Indians. Considering all these circumstances, the success of Austin and others in introducing Anglo-American colonists, was wonderful. If we inquire into the grounds of this success, we shall find it in the character of the men. They were brave, hardy, industrious men, self-helpful and self-reliant. They asked no favors of the Government, and the Government let them severely alone. Their stout arms cultivated their farms and protected their homes from the incursions of the savages. Volumes might be written, detailing instances of individual bravery—of hardships cheerfully endured by old and young, male and female colonists.

20,000+ more pages of Texas history, written by those who lived it! Searchable flash drive or DVD here

$129.95

‹ Back