By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

THE MURDER OF MRS LEE AND CHILDREN

J. Marvin Hunter, Sr.

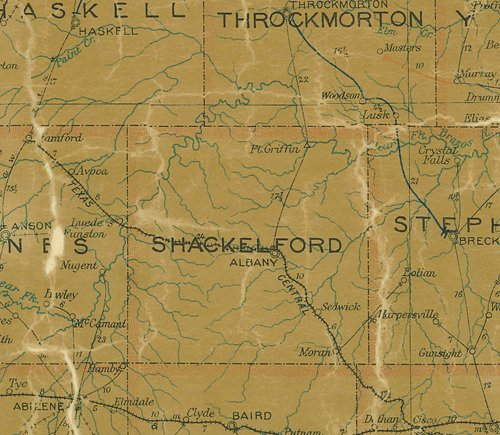

The Lee family, father, mother, and four children had homesteaded land about 9 miles from Fort Griffin, Texas, on the banks of the Clear Fork of the Brazos in the early 1870s. They had cleared land, built a log cabin, and had cultivated a patch of ground. It was early fall and they were preparing to gather a bountiful harvest. These simple folks were a typical pioneer family, who thanked God daily for their blessings, thanked Him for their peace and happiness, and for the ceasing of raids of the Indians. Early one Monday morning Mr. Lee arose and made preparations to go to Fort Griffin for supplies, intending to make the trip to the little frontier town and return before nightfall. After breakfast he hitched up his team to the wagon, kissed his wife and started out.

After clearing away the breakfast dishes, Mrs. Lee and her fourteen year-old son, went to the corn field, where they commenced gathering the corn, leaving her two little girls and baby at the house. They worked rapidly and talked but little. Nearing the end of the field that butted on the river bank, they paused to rest, wondering why a small herd of cattle that seemed frightened were running alongside the field fence. Turning around to look in the opposite direction, Mrs. Lee beheld the hideous face of a Comanche Indian staring at her through the parted corn stalks. Greatly alarmed, she and her son fled toward the house. Behind them rose the dreaded war cry, and a score of painted savages swiftly pursued them. Within a hundred yards of the home Mrs. Lee screamed a warning to her two daughters, but that was her last cry, for a shower of arrows ended the race and both mother and son were dead before the savages reached them.

Advancing upon the home, the savages found the doors barred, but they soon battered down a door. Crouching in the corner of a room were the two little girls, one holding the baby to her breast. The little girls were dragged into the center of the room while the warriors held a pow-wow. Snatching the baby from the older girl the chief took it in his arms and threw it upward. As it came down he drove a knife into its heart and cast the little body on the floor. Swiftly the Indians tied the two girls on horses and, before the noon hour, were far far away from the scene of massacre.

John Lee, returning at night with the supplies, suddenly became alarmed as he came in view of his little home. All was quiet and in darkness, and there was no light in the windows. That was unlike his wife, for she always waited up to greet him upon his return. He urged the team forward, and coming closer to the house, called to his wife, but there was no answer. Then he saw the door ajar. With heart beating fast, he leaped from the wagon and rushed into the house. By the flare of a match he saw the baby lying in a pool of its own blood, and noted the disordered condition of the room. He searched for the other members of his family and eventually found the murdered wife and son.

_____________________________________

_____________________________________

Soldiers from Fort Griffin pursued the Indians, but they had covered their trail well and pursuit was a hopeless task. They escaped and had taken with them the two little Lee girls as captives.

Several months after the massacre of the members of the Lee family, a big black negro rode into the post at Fort Griffin and asked to see the commanding officer. When ushered into the officer's presence the negro said: "My name is Johnson, and I is an adopted member of the Comanche Indians. I is fell out wid dem red devils, and I comes in to tell you dey has a white girl which dey is holding — got her married to one of de chiefs."

Next morning a detachment of cavalry rode out of Fort Griffin to an Indian village and rescued the Lee girl. It was a horrible tale she told and on her evidence several of the Indians were punished. The fate of the other little girl remains unsolved.

The Comanches realized that information of the Lee family massacre had been disclosed by the negro Johnson, and they sent him a message that they would kill him on sight, but the black was courageous and did not fear them. However, he went armed and took every precaution, for he realized if caught at a disadvantage the Comanches would murder him. Especially did he fear to meet them on Salt Creek prairie in his going to and from Jacksboro, therefore he always tried to cross this prairie in company with white men.

But a month later he was compelled to make the trip alone. He stayed in Jacksboro overnight and set out early next morning. Mounted on a good horse, he believed he could escape if attacked by an overwhelming number of Indians. As he neared the Salt Creek prairie he broke into song.

Suddenly his horse threw up its head and snorted. He loosed his rifle from its scabbard and looked around, then rode out on the prairie. Before Johnson realized what was happening three hundred braves had surrounded him. There was no running, he must fight. He leaped from his horse, and with the hundred cartridges in his belt, he commenced firing. Indian after Indian fell before his deadly aim, but on they came.

His ammunition exhausted and badly wounded, the negro finally came to a hand-to-hand battle with the Indians. He wielded his knife right and left, but superior numbers smothered him, and hours later a stage driver found his body badly mutilated.

Pioneers took the body of the negro and gave it decent burial.

Even unto this day children of these pioneers speak reverently of Johnson and will tell you that he was brave, a friend of the white race, and that he did not die in vain.

20,000+ more pages of Texas history, written by those who lived it! Searchable flash drive or DVD here

$129.95 $89.95 $49.95 (For a few more days!) BUY YOURS NOW

‹ Back

Comments