By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

THE MASSACRE OF JOHN WEBSTER AND PARTY

From J. Marvin Hunter’s Frontier Times Magazine, October, 1923

After Sam Houston’s decisive victory at San Jacinto, many people came to Texas from the older states. Many of them were single men, coming for the love of adventure and many of them were men with families coming to this land of beauty, fertility and promise to secure land and homes for their families. Texas was offering very tempting inducements to immigrants and many thousands were coming to take advantage of these donations of land since Texas had been able to throw off the Mexican yoke.

Among those people came John Webster and his family consisting of his wife and two children, a boy and a girl, an infant in arms, and one or more negro servants. They came from Virginia and with them came John Darlington, a young man.

Webster and family stopped at Webberville, in Bastrop County, and had title to a tract of land that is now in the county of Burnet, the little village known as Strickling, being on the tract then owned by John Webster.

At Webberville, in July and August, 1839, Webster gathered together an outfit, such as would be needed to make a home in a new country, consisting of Wagons, oxen, farm tools, horses, arms, and other things that pertained to a pioneer's outfit.

Webster knew of the danger from Indians for the brutal Comanches were in control of the country north and west of Austin. For protection from Indians and to assist him in improving his place, he induced eleven young men to accompany him, and tradition says he had with him a negro man servant and his wife, making the party consist of thirteen men, two women, including the negro woman servant and the two Webster children, making seventeen souls in the party. Between the 10th and 15th of August, 1839, this party took up the line of march, having three wagons, drawn by oxen. There being no roads and none of the men familiar with the country, their progress was very slow. According to Mrs. Webster's account, at about sundown on the third day they reached an elevation that overlooked the spot that Webster intended to make his future home. But to their horror a large number of Comanche Indians were encamped on the spot intended for the Webster home. A hasty council was held, and from the fact that the Webster party was so greatly outnumbered by the savages, it was decided to make their way back to Webberville, to get reinforcements.

The party then took the trail they had made in coming and made all haste they could with their slow moving oxen, hoping that the Indians had not discovered them. A vain hope, however, as the sequel shows.

The party made good progress on their retreat, the darkness being considered, until they crossed the South San Gabriel. This point is three miles north of the town of Leander in Williamson County, and the crossing was between what is known as the Cashion farm and the Wilson farm, where a spring branch empties into the San Gabriel. Going out of the San Gabriel Valley, the foremost wagon was hung onto a tree in such a manner that it was impossible to get it off without cutting down the tree, and this was slow work underneath the wagon, and in the darkness. Had it been the rear wagon, it could have been abandoned, but was the front wagon, and blocked progress. Mrs. Webster said several hours were lost in extricating the wagon.

About sunrise the yelling Indians came in sight. The Webster party had reached the Brushy Creek Valley near the north bank of brushy Creek, a bluff some twenty feet in height and over 150 yards in length formed the north bank of the creek. Some of the party proposed to abandon the wagons and take refuge under the bluff, but the only protection from the south would have been a fringe of trees growing along the creek. Little time was permitted for a discussion, for the Indians were preparing to attack. A corral, such as only three wagons could make, was quickly formed, the oxen taken loose from the wagon tongues, and all parties took refuge in the corral and under the wagons and prepared the best they could for resistance.

The Indians would form on a low ridge, having some scattering post oak timber on it, then they would charge, going by the wagons, and shooting at the Webster party as they passed, Webster and his men firing at the Indians as they passed. This kind of an attack was kept up until in the afternoon, and until all of the men were killed, leaving only Mrs. Webster and the negro woman and the two Webster children living, better protection being given them by some of the household goods.

The scene of this bloody tragedy is located one mile east of the flourishing little town of Leander, on the Llano branch of the Houston and Texas Central Railroad, about thirty miles from Austin.

The Indians burned the wagons, carried off such articles as they wanted, and took up their line of march in a northwesterly direction, taking Mrs. Webster, her two children and the negro woman as captives.

_____________________________________

Love Texas history?

_____________________________________

Webster's friends at Webberville, hearing nothing from the party, none of the men returning, a party was sent out on their trail to look for them. Of this party was Henderson Upchurch, afterward a prominent citizen and farmer of the Leander community, and from his family much of the matter of this article. was obtained, as Mr. Upchurch has been dead many years.

Mr. Upchurch and his party found some of oxen making their way back to Webberville, with the yokes still on some of them. A few miles further on, after finding the oxen, the party came upon the remains of the wagons and the bones of the unfortunate Webster party. This party returned to Webberville and reported, and another party was made up to bury the victims of the massacre. Of this party was George Alley, who afterwards lived and died in Georgetown and Rev. Jack Atkinson, a pioneer preacher of the Cumberland Presbyterian church.

Mr. Atkinson said the bones of the victims were scattered over the little valley where the battle occurred for several hundred yards in the tall grass, making it difficult to get all the bones together. Wolves had dragged parts of the bodies for a long distance.

Tile Websters had packed their bed clothes in a crockery ware crate, which was not destroyed by the indians. In this crate they gathered the bones of the thirteen men and buried them near a clump of live oaks, not far from where the wagons were.

Mrs. Webster and her children were taken to the mountain country at the head of the Guadalupe and Llano Rivers. She and her children attempted to escape and were recaptured, according to her description of the country, somewhere near Pilot Knob, a few miles north of Austin. Some time during the next summer, Mrs. Webster escaped from the savages at the head of the Guadalupe River, taking with her her baby daughter, and after many hardships and great suffering came in sight of San Antonio. She was entirely destitute of clothing, and on this account remained hidden in the mesquite brush near the city until nightfall, when she went into the city and told her story. She was kindly cared for and all her wants supplied by Mrs. Maverick and other kind-hearted ladies.

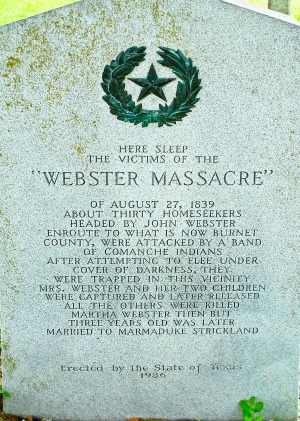

She was restored to her friends, and the boy was rescued by traders among the Indians. The daughter Martha V. afterward married a man by the name of Strickling and spent her life in this part of the State. A number of years after the Indians were driven back, a monument was erected over Webster's grave. It was made of soft limestone of that region, and time and weather have turned it almost black, and the letters can only be deciphered by tracing them over with white crayon.

The inscription is as follows: "To the memory of Washington Perry Reese and William Parker Reese, killed with John Webster and Company by the Comanche Indians, Aug. 27, A. D. 1839. This tomb was raised by their brothers and Webster's daughter, Martha V. Strickling: Charles K. Reese and Thomas Reese."

This place has been made a cemetery and is known as the Davis Graveyard, where rests all that is mortal of many good pioneer citizens who came after the wild Indians were driven back. That beautiful valley in 1839 was a sea of waving grass, interspersed with a few trees, then the scene of heart rendering tragedy, is now green with growing cotton and waving corn dotted with comfortable homes, churches and schoolhouses, telegraph and telephone wires, broad public roads, along which speed the flying automobile; trains on the railroads, carrying the products of a happy and prosperous people to the ends of the earth. Indeed, we can exclaim, "See what God hath wrought."

20,000+ more pages of Texas history, written by those who lived it! Searchable flash drive or DVD here

$129.95

Option 2

Get 352 issues packed with stories like the one you just read

$99.95

‹ Back

Comments