By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

THE FRAZER-MILLER FEUD

From Hunter’s Frontier Times Magazine, November 1944

When Jim B. Miller was hanged by a mob of citizens at Ada, Okla., last summer there ended the career of the worst and most dangerous of all the bad men who in the old days made a practice of man killing, and when the wires flashed the news throughout. the length and breadth of Texas there was rejoicing in many places where Miller had formerly lived.

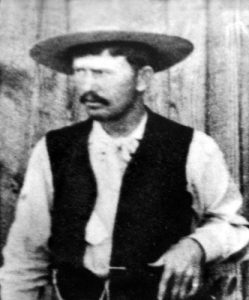

Along in the early '90s Bud Frazer was sheriff of Reeves county, of which Pecos is the county seat. Miller came out to Pecos from his home in Central Texas and was soon employed by Frazer as deputy. Several years before this he was indicted, tried and convicted of killing a brother in law and given a life sentence, but a new trial was secured, and when the case was called the second time many of the witnesses had disappeared and Miller came clear. He was only 22 years old at the time and the murder was a most atrocious one. The man was shot as he lay sleeping on his porch at night. Frazer was warned of his character and advised not to employ him, but he did, and for a time all went well.

One day he sent Miller in charge of a Mexican prisoner, who was being moved to Fort Stockton for trial. Miller returned and reported that the Mexican had made an attempt to escape and he had killed him. No one was present when it occurred except Miller and the Mexican, so he was cleared. The people thought the killing was unnecessary.

Some months later the ranches began to lose stock, and it was discovered that they were being driven south across the line into Mexico. Frazer got busy on the case and his investigations soon led him to suspect that Miller was mixed up in the theft. Miller in some way learned of Frazer's suspicions, and one day Captain Hughes and his rangers came down to Pecos and arrested Miller, his brother in law, Manen Clements, and two other parties on the charge of entering into a conspiracy to assassinate Frazer. It seems that, while the conspiracy was hatching, some one of them approached a man named Con Gibson and asked him to join them. He refused, and told Frazer of the plot, thereby causing the arrest of them all. On examining trial all were turned loose except Miller and Clements, and they were indicted and afterwards tried at El Paso and cleared of the charge. They were defended by Judge Walthall and Senator Turney.

A short time later Con Gibson went to Eddy, N. M., to live and was there murdered by John Denson, a cousin of Miller's wife, who had some time before made an attempt to murder the sheriff there but failed. The murder of Gibson was a most cold-blooded assassination, but Denson was surrounded by his friends at the time and they swore him out of it when the case was tried. He had no quarrel with Gibson, and people knew that Gibson's testimony against Miller had cost him his life

Later on Frazer and Miller met on the streets of Pecos one day and Frazer opened fire on Miller with a six-shooter, wounding him through the right arm and side. At the next election Frazer was defeated and moved to Eddy, N. M., for a while, but later returned to Pecos, where he and Miller again had a shooting scrape. Frazer was armed with a repeating rifle and Miller with a double-barrel shotgun. Miller was wounded again, but recovered. Frazer was tried at El Paso and the case resulted in a hung jury. Later he was tried at Colorado City, Texas, and acquitted in both cases. Just before the first trial, John Wesley Hardin, a cousin of Miller's wife, came out to Pecos. He was a noted man killer of Texas, and had just finished serving a long penitentiary sentence when he arrived in Pecos. While in the pen he had studied law and had been admitted to the bar and was employed by Miller to prosecute Frazer. He came to El Paso to be present at that trial and remained here. He began life early as a man killer. it was right after the civil war and Texas, like all the Southern states at that time, was in the throes of reconstruction. E. J. Davis, a. notorious carpetbagger, was governor, and he had organized a band of negro police who were overrunning the state and terrorizing women and children. Hardin, who was a mere boy at the time, did something they did not like, and they went out to arrest him. The result was that he killed several of them. From that time on there was war between him and the negro cops, and he always came out ahead of the game. Texas was very unsettled in those days, and killings were so frequent as to excite but little attention, but by and bye, when things settled down, and John Wesley kept on killing people, they thought it was' time to call a halt, and so finally he was arrested, tried and convicted and given a long sentence, which he served.

When he appeared in El Paso he was a quiet, gentlemanly kind of fellow, and people felt very kindly toward him. El Paso, at the time he came here, was a wide open gambling town, and he soon began frequenting the games and ere long was having trouble. He was "quick as lightning" with a gun and a dead shot, therefore he was greatly feared. He was finally killed in the old Acme saloon on San Antonio street by John Sellman. Sellman came clear, and some time later was himself killed by George Scarborough, who in turn came clear and was afterwards killed by a band of outlaws in the mountains of New Mexico. All of these were "gunmen" who had before killed men, and like all man killers, they died with their boots on.

After Frazer's acquittal at Colorado City he came to El Paso, where he lived for a time. One day he took the train for Toyah, Texas, a small town twenty miles from Pecos, also in Reeves county. An election was approaching and he intended to work for some friends of his who were candidates. Miller heard he was there, and in some mysterious way got into Toyah and into a room at the hotel during the night without having been seen by anyone. From the window of his room he could plainly see the house where Frazer was stopping, also a saloon between the hotel and the house, After breakfast, Frazer came out of the house and walked over and entered the saloon, never dreaming of danger. In the saloon he met a party of friends and someone proposed a game of seven-up, and soon they were sitting about the table, busy in the game.

Seeing him enter the saloon, Miller slipped down the rear stairway, across the backyard and out a side gate, and the first thing the players in the saloon knew the door was pushed open by his double-barrel shotgun and a double report followed. Frazer rolled over dead, without ever knowing who fired the shot. A man named Earheart occupied the room where Miller was supposed to have passed the night and this fact was the cause of him being involved in the feud. Heretofore he was not supposed to be friendly with either side. He was generally regarded as a quiet, peaceable man, except when drinking, and people never understood why it was that he harbored Miller in his room overnight when it was plain that murder was intended. After the killing of Frazer, Miller returned to Pecos, where he was running a hotel, and where he harbored several hard characters. The hotel resembled a fort, and people feared to speak their thoughts. Miller gave it out that there must be no talking.

Now—it is a peculiar fact that the worst of men always have friends among good, law-abiding citizens, and it was so in this case. The town was divided one-half against the other. The lodges, the churches, neighbors, friends, all became divided, and the feeling was very bitter. Right after Miller was tried in the conspiracy case he joined the Methodist church during a revival, and as he was of a quiet disposition and never swore or went about saloons, many people believed him to be different from what he really was, and many were ostensibly his friends through fear of him. It was said at the time and generally believed that two or three wealthy men in that section put up for him considerable money with which he employed attorneys for his defense. To look at him he was the last man on earth one would take to be a desperate character, and yet he was, of all the bad men, the worst. He would fight a man in a fair face to face gun fight, or he would lie in wait and assassinate him. He would murder for revenge, or he would murder for money. It was said of him that he first tried his case, then murdered his man. Be that as it may, he always had a loophole of escape—always a self-defense, an alibi or something, and time after time he escaped the vengeance of the law. Always he had a gang of men whom he controlled, scattered about the country, ready to do his bidding. He was the chief, the leader, and when he got into trouble they were ever at hand to assist him in getting out. He was indicted for the killing of Frazer, and the case was moved to Eastland, a small granger town way down on the T. & P., this side of Fort Worth. He moved down there, rented a hotel and began to make friends and get ready for the coming trial. He moved his church letter there and united with the church in Eastland. Some of his Pecos friends wrote letters commending him to their friends in Eastland, and so by the time of the trial he had worked up a feeling of sympathy for himself. When court convened there were 150 witnesses from west of the Pecos river alone. Among those from El Paso were Frank Simmons, Joe Escajeda and Tom Bendy. The report had gone out that all the bad men from West Texas were going down there to attend that triaL

A large number of railroad men had been summoned from Toyah, and there being scant hotel accommodations at Eastland for such a large crowd, the T. & P. company sent down a tourist sleeper and switched it off there for their accommodation. The report got out that a hundred Winchester rifles were on the car, and great excitement prevailed. It was even suggested by some of the frightened villagers that the local militia company be called out to keep the peace. Every farmer for miles around was in town to see the bad men from out West. It was surprising to find how little those people knew of West Texas. It was in the summer and at a time when people in that section have very little money. Now the Westerner always spends his money like a lord—be it much or little—and it was not long before those grangers began sizing up everyone as a cattle king rolling in wealth. A crowd of county convicts were on the street at work. Among them was a boy about 14 years old, who was serving a sentence for some trivial offense. He made a dash for liberty, but was caught and returned. A crowd gathered around and soon made up money to pay his fine, and he was set free. This act of generosity greatly surprised the close-fisted natives, and they could not understand it.

The trial was long and hard fought, and resulted in a hung jury. Good church members from Pecos testified that Miller's character was without reproach, and one good deacon swore that his conduct had been exemplary as that of a minister of the gospel. Six months later the case was tried again in the same town and Miller was acquitted.

It was said that Miller never met but one man whom he feared. That man was Barney Riggs, a brother in law of Frazer. Riggs was a gunman and had had a most peculiar experience. Raised in Texas, he went to Arizona when yet a young man. He had just married and soon secured a job as foreman on a ranch. One day he suddenly discovered that his employer had ruined his home, and without ceremony shot him dead. The man he killed was rich, while Riggs was poor, and a stranger. Moreover, in those days Texans were not over popular in Arizona, and the result was that Riggs got a life sentence and was sent to the territorial penitentiary at Yuma. After he had been there for some time a few of the more desperate prisoners hatched a plot to kill the warden and escape. A few arms were smuggled in and at the appointed time the attack was made. The warden had treated Riggs welt and he was a trusty. Seeing them make the attack, he ran in, knocked a man down, seized his knife and with it killed two convicts before the guards ran up, and seeing Riggs with a bloody knife in his hand, they began shooting at him, thinking he was attacking the warden. For this act of bravery Riggs was pardoned, and then moved back to Texas, where he married, some years later, a sister of Bud Frazer. He often said that he was the only man on record who killed a man and got in the pen and then killed two and got out.

At the time Miller killed Frazer everybody predicted trouble between him and Barney Riggs. One day there was a circus at Pecos and Riggs and his family came in from the ranch to see it. John Denson and Bill Earheart were in town stopping at Miller's hotel. Everybody looked for trouble, but none came that day. Next day Riggs hitched up his team to go home, and went into a saloon to get some articles he had left there. Denson and Earheart were both there and drinking. They met and drew—when the smoke cleared, Earheart lay on the floor, shot through the brain, while just within the door lay Denson with a 45 calibre bullet through his head. Riggs was tried at El Paso and acquitted. Jack Edwards of El Paso and Judge Hefner of Pecos defended him. He was killed some years ago by Buck Chadborn, his step son in law, at Fort Stockton. Riggs was the aggressor, and Chadborn, who was a mere boy at the time, was acquitted of the charge.

It was often predicted that Miller and Riggs would meet some day and have it out, but fate decreed otherwise. Both men were "dead game," and had they ever met in a six-shooter contest it is hard to tell how it would have resulted.

Riggs had five notches on his six-shooter when he cashed in with his "boots on," and Miller many more.

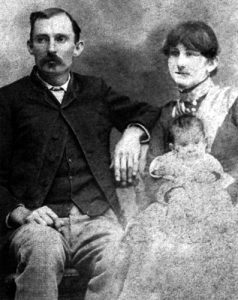

After being acquitted of the conspiracy charge against Frazer, Manen Clements moved to El Paso and cut loose from Miller. He and Frazer patched up their difficulties and were fairly good friends to the day of Frazer's death. Manen settled down and was given a position on the police force, which he filled for some years, and was then elected constable, which office he held until just prior to his death. He finally met his death in the Coney Island saloon at the hands of parties unknown.

After being acquitted of the murder of Frazer at the "postoak town" of Eastland, Miller did not seem to prosper. The trial had brought out enough bad traits of his character to convince those law-abiding, God-fearing granger people that Miller was not all to the good. So he moved to Fort Worth, Texas, where he soon got into trouble again. This time it was on a charge of perjury, and he was given two years in the pen. He secured a new trial and again came clear. It seemed impossible to get him in a legal way. for every time he escaped free from the meshes of the law.

He then returned to Fort Worth and opened up a hotel. A few months later he again killed a man and again escaped free. About this time trouble arose between cattlemen and settlers out in Ward county in the Pecos Valley. and Miller was employed by some cattlemen to intimidate the settlers. During this time he visited Pesetas, but even his old friends who had sworn him free at his trial for killing Frazer did not warm to him as of old, and he did not receive a very royal welcome. He returned to Fort Worth, where he continued to scheme and concoct plans for more outlawry. It is said that on one occasion he bought a bunch of mules, giving in payment a worthless check. When it was discovered that the check was worthless the holder pocketed the loss and said nothing. He feared for his life and felt that it would be better to lose the money than to lose his life. It was claimed that Miller pulled off several deals of this kind while in Fort Worth, Also that he had a hand in two or three mysterious killings in various parts of the state. Finally the drifted off up into Oklahoma, and that fact proved his undoing. Fate was drawing the lines close about him, and his career of crime was drawing to a close.

The killing he pulled off there was a most bungling affair. He failed to "try the case before killing his man." It was utterly unlike Miller's methods. He left many broken places in his fence. The proof was plain and clear against him. Why he did not do a better job of it no one knows. Perhaps he had escaped so often that he had come to the conclusion that he was invincible and could not be convicted. He had no quarrel with his victim—did not know him, in fact. He murdered him for money. Even then it was said that people in Fort Worth went up there and offered to make bond for him up to $100,000. It was marvelous the way he could bring men with money to his aid when in trouble.

But those Oklahoma people had no idea that he should escape this time. Perhaps they had heard how slippery he was. One dark night a mob appeared at the jail and then Jim Miller realized that his course was run. Justice had at last called for an accounting. What must have been his thoughts during the few minutes the mob spent in beating down the doors? Did the many crimes he had committed flash through his memory? No one knows. A rope was fastened to his neck and he was raised just clear of the ground, and there slowly died. When the wires flashed the news over Texas there was rejoicing. Letters and telegrams poured into Ada. One telegram read: "Oklahoma is to be congratulated; she is up to date."

A short time before Miller was lynched, Manen Clements had met his death in El Paso. No one knew who did it, although the saloon was full of people at the time.

Miller told an acquaintance that as soon as he got out of his trouble in Oklahoma he was coming to El Paso and he would soon discover who killed Clements. Had he lived, there is no doubt but that El Paso would have seen something of him and perhaps another bloody chapter would have been added to the story of his life. But he never came. The hangman's rope cut short his career and he died like his victims, "with his boots on."

When Pat Garrett was killed it developed that Miller had been in that section. People who knew Miller and his methods best have always believed that he was in some way at the bottom of the affair, and they will never be convinced to the contrary. Thus ends the story of the bloody Frazer-Miller feud. With the death of Miller the last bad gunman of Texas passed into history. There will always be killers, but the regular man killer is a thing of the past in Texas.

It is peculiar that most of the victims of this feud were shot through the head. They were Frazer, Hardin, Denson, Earheart, Gibson and Clements. This does not speak well for the fairness of the old time Texas gunman. There is ordinarily nothing fair about such men. The victim has no show whatever for his life. Another peculiar thing is that not one of them were ever convicted—nine murders and not a single conviction. This of course does not apply to Hardin's early history.

This feud ran for about 18 years and ended in 1909 at Ada, Okla.

______________________________________

How about 20,000+ pages (352 issues) of Texas history like the one you just read?

$49.97

Use coupon code “half-off” at checkout

______________________________________

‹ Back

Comments