By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

SHANGHAI PIERCE - COLORFUL COWMAN OF TEXAS

From J. Marvin Hunter's Frontier Times Magazine, February, 1951

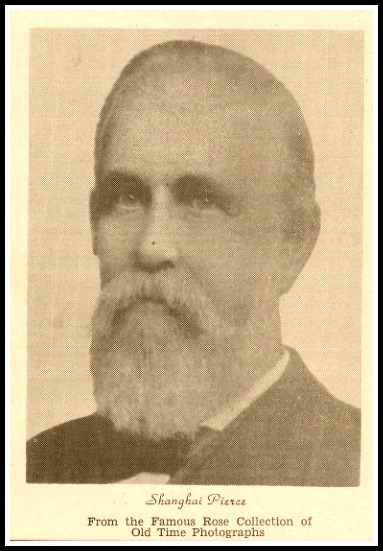

"Shanghai" Pierce, pioneer Texas cattleman, who erected a monument to himself on the theory that if he did not do so during his life, he might be forgotten in death, has been the subject of innumerable stories, but none perhaps, is more colorful than that which follows. The facts are furnished by A. C. Pyne of Victoria, who imagines that the unseeing eyes of "Shanghai" Pierce, on top of his monument, which stands in the old churchyard on the banks of Tres Palacios Creek might even now be "sweeping the mighty reaches of the plains over which he ruled, watching a ghostly herd, with the moonlight glinting on a sea of horns, sweeping up to the home corral."

It was in the very nature of existing conditions that the character of those hardy spirits who survived the vicissitudes of pioneer days in Texas should be positive in its every fiber. Historians are wont to refer to them as "diamonds in the rough," and that term, perhaps more than any other, aptly describes them.

A more refined generation may deplore their lack of culture, but none will deny that their blood was red, that they lived and died according to their convictions, and left behind them as their monument, the greatest state in the Union.

Among all that rugged crew whose hands fashioned an empire in the face of every known adversity, there was not a more picturesque character than the Yankee immigrant boy who made himself the "king of kings" in Western cattledom. Landing on the tidal flats of Southeast Texas "poorer than skimmed milk," he pursued a single idea until the name of Old Shang Pierce was a power wherever the longhorn bellowed.

Abel Head Pierce was born in Little Compton, R. I., June 29, 1834, and came to Texas in 1857. Of massive build and possessed of a powerful, bell-like voice which he could easily make heard for a mile, he acquired the nickname of Shanghai while still a boy in his native town. In jocular moments of his later years he was apt to say of himself: "By —, sir! I'm Shanghai Pierce, Webster on cattle..." It was by this name that he was known to thousands who would probably have recognized him by no other.

His first job after coming to Texas was with W. B. G. Grimes, who was operating an establishment near the mouth of the Colorado River. Grimes was one of the earliest of the Texas cattlemen, and at that time the largest on the gulf coast. Here the late arrival from New England launched his first venture in the cattle business by investing his wages in cows which had young calves. These cows were poor culls which the budding cattle baron bought for $14 a head when the pick of the range was worth $7. A severe winter followed and spring found Pierce relieved of all responsibilities as a cattle owner. This is what Grimes called "teaching a Yankee the cow business." But Pierce proved to be one of those rare pupils who profit by their lessons, and Grimes was to one day sit at the knee of this same Yankee and take some expensive lessons of his own in high finance as related to longhorn cows.

There is a story told of how, when Pierce first landed in Texas, he went to the ranch of an old Southern aristocrat looking for work. The owner was living up to the traditions of his Dixie forebears by sitting on the front veranda, sipping a mint julep. Upon approaching the old gentleman, Pierce was told that poor whites were received at the back door with the negroes. Whereupon Pierce turned and walked off, vowing that he would someday come back and buy the place, lock, stock, and barrel. Whether this story illustrates the grim determination of this transplanted son of New England or whether it is just another story, the fact remains that this ranch became a part of the vast domain over which he later ruled.

By the close of the civil war, Shanghai and his brother Jonathan had established the Rancho Grande at Deming's Bridge on Tres Palacious Creek in Matagorda County, a few miles from where the town of Blessing now stands, and were branding cattle over a territory more than 50 miles square. The cattle baron was arriving and the bellow of Shanghai's "sea lions" equalled only by the bellow of Old Shang himself, was destined to be heard throughout the cattle markets of the entire nation.

_____________________________________

_____________________________________

In the years immediately following the civil war, Shanghai occupied a position never attained by any other man in the cattle markets of the West, and at one time threatened to control the whole industry. Men returning home from four years fight in the Lost Cause, found their lands overrun with cattle which were not second in wildness to the jack rabbits and equally valueless. A Texan's only assets in those days were his lands and his cattle, and there were few men optimistic enough to attach any value to either. Their experience with Confederate currency had made them skeptical of paper money and "hard money" in Texas was notoriously conspicuous by its absence.

Shanghai Pierce realized that the future of Texas hinged upon finding a market for the only commodity it had to offer in salable quantities. The eastern half of the United States had just been ravaged by four years of desperate warfare, and they needed cattle. Texas had the cattle. True, they resembled a cross between a cyclone and a road runner, but they had horns and a bellow, and Eastern buyers were not being critical. The East had the market and Texas had the cattle, and Pierce could foresee the possibilities which lay ahead of the man who could bring these two together.

He was among the first to trail his herds north to meet the railroads which were beginning to push their way into the Southwest. Returning from these drives. he brought back gold and silver which he exchanged for other herds to drive north. To the men from whom he bought these herds, he was literally a gift from heaven, for many of them whose cattle numbered thousands, hadn't possessed as much as $100 at one time in more than four years.

On his trips about the country buying cattle, he was accompanied by a negro leading a mule loaded with bags of gold and silver. When the cattle had been gathered and received, he would empty the bags on a blanket and count out the money to pay for them. While waiting for a herd to be rounded up, he often remained in camp for a week or more, where his endless store of wit and anecdotes assured him a welcome around the chuck wagon and campfire.

Mr. Pyne remembers a story told to him as a boy by an old Texas cowpuncher many years before the name of Shanghai Pierce came to have any significance to him whatever. Among the men in his employ was a Mexican who had worked for him for a long while. In common with many cowboys, he had only drawn sufficient of his wages for his living expenses, leaving the balance to accrue to his credit until at the time of the story Pierce owed him more than $100. On one of his trips north the old cattleman brought back a coffee mill, a small box affair, containing a drawer for holding the ground coffee, and surmounted by an iron hopper holding about a cupful of unground coffee and the burrs necessary for grinding it. It was operated by holding it between the knees and turning a small crank.

The Mexican had never seen one of these strange affairs. He approached his employer to ask the cost of this wonderful machine. Shang, scenting a profitable trade, placed its value at a figure slightly in excess of the amount which he owed the Mexican, who immediately lost all interest in the coffee mill, much to old Shang's disappointment. Not long after this, the cook went to grind his coffee one morning and couldn't locate his coffee mill. Needless to say the Mexican was AWOL also. Old Shang spent several minutes picturesquely cussing the Mexican thief, but made no effort to apprehend him.

His detractors have told many stories about this old giant which were uncomplimentary, and that his detractors were numerous is attested by the fact that he once said: "By —, sir! If I was to stop to fight with everybody who cussed me, I would be fighting all the time, but while they are busy cussing me, I am busy getting their money." That he was a forceful, dominant character must be granted, for in no other way could he have become a leader among the men with whom he dealt. He was a descendant of pioneer Rhode Island and Virginia families, possessed of a brilliant intellect and no mean education, but in the cattle country his manner conformed to the modes prevailing in the best cow circles. In ordinary conversation his voice could be heard for four blocks, and his vocabulary was picturesque, rather than elegant. But Shanghai Pierce was a cattleman, and it has never been recorded that longhorn cows or the pioneer men who handled them were ever prostrated by a college education or drawing-room manner.

On his trips to Wichita and Abilene, he has been pictured as a habitue of saloons and gambling halls, and surrounded by a gang of swashbuckling Texas gunfighters. One writer tells a refreshing tale of how old Shang and his entire crew were cowed and unarmed single-handed by the redoubtable Wyatt Earp, armed with a shotgun.

In common with most men of his time, it was his custom to drink a glass of whiskey whenever he felt that the occasion demanded it, and the whiskey barrel at his home was never empty. But that he ever drank to excess on any occasion is emphatically denied by all who knew him.

Of the Wyatt Earp episode I can find no witness, but one man, who was associated with Earp for many years, believes it the outgrowth of a tale told by a Texan and a well known character in the cattle business who used "Old Shang" to embellish his narrative. This same man also said he was told by Ben Q. Ward, who knew Pierce intimately in those days, that Pierce's mind then was concerned with a big plan to corner the cattle market and that Earp had small chance to meet Pierce along the cattle trails leading out of Abilene or Wichita, where the alleged episode is supposed to have taken place.

When the railroads came, Mr. Pierce moved his headquarters to their present location in Wharton county, where he established the town that is named for him. While he never succeeded in cornering the cattle market, he remained an important power in the industry a s long as he lived.

Some time before his death he had a life-size statue of himself cast in bronze. This statue has been used to embellish more than one story of the old cattle baron's ego and love of the sensational. The only reason which he is known to have given himself is contained in the single remark: "Sir, if I don't do it myself, they'll forget Old Shang." A better reason perhaps could be found in a desire to outdo his old friend Ben Q. Ward, who had assured his own commemoration to posterity by having a bust struck.

While on a trip through the Orient, Mr. Pierce conceived the idea of introducing Brahma cattle to the coastal plains as a means of combating the tick fever to which native cattle were subject. After his return, he bought two old Brahma bulls from a circus, and while these proved worthless for breeding purposes, they proved conclusively that there was a line beyond which even a Texas tick refused to go. In this case it was sacred bulls. This project lay fallow until some years after Mr. Pierce's death in 1900, and was carried out by his nephew, A. P. Borden, who went to the Orient and brought back the first herd of Brahmas ever imported to Texas from India. Today these curious hump-backed animals may be seen throughout the coastal regions where their massive frames bear witness to the sagacity of the man who fostered their coming.

On the banks of Tres Palacios Creek stands an old weatherboarded church, long since abandoned, and slowly decaying in the sun and rain. In the old tower, the bell which in bygone days sent forth it's call to worship across the plains, has fallen from its moorings. its tongue is stilled. Close by this old church is a grove of majestic oaks whose streamers of Spanish moss sway gently to the caress of a Texas breeze, has been reared a granite shaft. This shaft marks the plot, where beside the wife and baby son who had awaited his coming for 30 years, lies all that was mortal of the man who was loved, respected and hated as "Old Shang" Pierce. On top of this shaft, unseeing eyes sweeping the mighty reaches of the plains over which he ruled, stands his bronze replica in eternal silence. But when clouds fleck across the face of the moon we can stand beneath the giant oaks and imagine that once again he is watching a ghostly herd with the moonlight glinting on a sea of horns, sweep up to the home corral. And we hold our breath in silence, straining to catch the first note of that mighty call with which he greeted their coming in days when Texas was young.

The mossy horn has followed the master herdsman to the shores of Ashpodel, the huisache and the chaparral will know them no more. The trails they roamed are marked by threads of shining steel and ribbons of glistening concrete. Cattle of a gentler breed graze beside broad acres of snowy cotton in the thickets where once they reigned supreme. The branding pen has been replaced by beautiful homes wherein dwell men and women who were cast in a less stern mold. Happy, healthy children romp and play where once the old "brush popper" spread his blankets, beneath the Texas skies. And in these things have been builded to them the only monument befitting the monarchs they were.

Hunkering down?

Immerse yourself in rich TEXAS history, written by those who lived it!

Click HERE to start reading 352 issues (20,000 + pages) of Rich Texas History -

Written by those who lived it!!!

‹ Back