By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

Pearl Hart, Arizona Woman Bandit - J. Marvin Hunter, Sr.

[From J. Marvin Hunter’s Frontier Times Magazine, January, 1950]

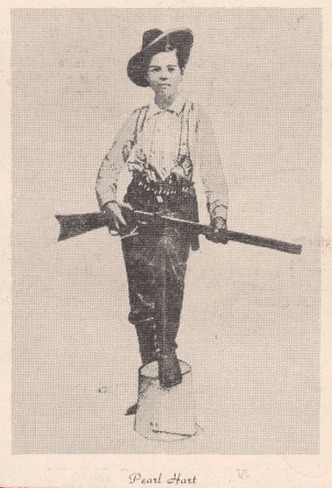

ON our cover this month appears the portrait of Pearl Hart, a good girl spoiled by misfortune's cruel hand. When I saw Pearl Hart in Deming, New Mexico, in February, 1901, she was dressed just as you see her in the cover page photograph, with the exception that she wore a coat and vest, and easily passed as a young man about nineteen years old. George Scarborough, a well known officer of that section, arrested her at the Southern Pacific depot in Deming and placed her in the small wooden jail of that place, and that night she broke out of the little calaboose, and the next morning Scarborough took her trail and recaptured her out on the desert fifteen miles west of Deming, hot-footing it back to Arizona. Pearl was charged with being implicated in a train hold-up which was staged near the New Mexico-Arizona line, but there was not sufficient evidence to convict her and she was released. She had previously served a little more than two years of a five-year sentence in the Yuma penitentiary for robbing a stage driver near Globe, Arizona, in 1899. The following article appeared in the Coconino (Arizona) Sun, November 25, 1899:

"Pearl Hart, the female bandit, is now in the territorial penitentiary, where she will likely remain for the next five years, less time for good behavior, which she will not earn unless she adopts a mode of life different from any she has followed since she came to Arizona. A fool jury of Pinal county having acquitted her of a charge of holding up a stage, and having been discharged by Judge Doan in disgrace, another jury found her guilty of robbing Henry Bacon, the stage driver, of a revolver and other property. She was sentenced to five years at Yuma. Passengers who came in from Maricopa yesterday say she was taken past there early in the morning with a big cigar in her mouth rivaling the efforts of the locomotive to charge the atmosphere with smoke."

Pearl Taylor was born in the little town of Lindsay, Ontario, Canada, about 1871. She attended a boarding school there and in her seventeenth year, met a man named Hart, who persuaded her to elope with him. They were married and lived happily together for a short time, and then he began to abuse her. He drove her away from their home by his continued cruel and inhuman treatment and she went back to her old home with her mother, where she remained only a short time. Her husband sent for her and, under promise of kind treatment in the future, she returned to him. For about two weeks he treated her with the utmost kindness and consideration and then again began to abuse her, even resorting to beating her frequently. This was in the fall of 1893 and she left him once more, and wishing to get as far away from him as possible, Pearl went to Trinidad, Colorado. For many months she wrestled in a catch-as-catch-can style, making only a scanty living for herself and baby boy, who was born while she was back in her home town with her mother. She went from one town to another and finally landed in Phoenix, Arizona, where one day she met her husband face to face on the street. She still loved him and, in spite of knowing that if she went back to him she would not be happy, and fight as she would against the temptation, her love for him won out and she went back to live with him once more.

They lived happily together in Phoenix for about three years and during this time a baby girl was born to them. Then her husband began to abuse her again, and she left him for the third time. She sent her two children to her mother in Canada, and went east and obtained employment in a well-to-do family as a servant girl.

During her two years' stay in the east she heard of her husband occasionally. She tried to forget him but her efforts along this line were unsuccessful. He was the father of her children, and she still loved him. He finally found out where she was and went to her, and with his bland and alluring promises he once more persuaded her to return to Arizona and live with him. They located in Tucson, but as he was absolutely worthless and did not make any attempt at making a living for them, the money which she had saved during her two years' servitude in the east was soon gone, and he again began abusing her, until 1898, when he joined McCord's Regiment of Rough Riders and left town.

Pearl went to Phoenix and managed to get along after a manner. She tried two or three times to commit suicide, but was prevented by the interference of friends. Finally she obtained employment as cook in a mining camp at Mammoth, Arizona, and worked there for several months, but as her living quarters consisted only of a tent, pitched on the bank of the Gila river, her health began to suffer. She loaded all of her worldly possessions onto a freight wagon one day and started for Globe, but the roads were so muddy that the horses were unable to pull the wagon through, and they turned back, and Pearl once more landed in the mining camp at Mammoth.

A few days later a man named Joe Boot, wishing to go to Globe, made arrangements with a couple of young men to take himself and Pearl Hart to Globe. The roads were so bad that they made only three miles the first day and camped. The following day they managed to reach Globe, where Pearl obtained employment in a miners' boarding house, which position she held until one of the big mines there shut down and she was once more left with nothing to do. Pearl had saved a little money from what she had received for her work, but just about that time one of her brothers, who had located her, wrote that he was in trouble and for her to send him all that she could spare.

Before she could locate another position, her husband once more appeared on the scene, having been mustered out of the army at Tucson. He was too lazy to work and insisted that she support him, but she refused to do so in the manner which he suggested, and they quarreled and he left. She never saw him again.

Just before her husband left Globe, she, being broke and having no job, received a letter from home stating that her mother was very ill and not expected to live, and that if she expected to see her alive she must come at once. She fairly idolized her mother and this knowledge that her parent was liable to die at any minute, and the realization that she had no money to pay her railroad fare to her mother's bedside, nearly drove her frantic. Pearl herself said she believed that brooding over her misfortunes drove her temporarily insane.

Joe Boot located what he thought was a profitable mining claim, and suggested to Pearl that they go and dig out enough dirt to get her home. She donned men's clothing and went out to the mine, and they worked night and day, but it was useless. She wielded a pick and shovel and did a man's work on the claim until every vestige of color had faded away. Joe Boot sympathized with her as a true friend should, but he had no money and was powerless to render her any assistance, as it was impossible for him to get enough money on such short notice to pay her expenses home. He finally proposed to her that they rob the Globe stage, and though at first she refused to take any part in any such enterprise, after brooding over her trouble for awhile, she finally weakened and consented, after she had made Boot promise that no one would be hurt. Boot assured her that it was easy enough, for all that was necessary was to put on a bold front and that the rest would be easy.

On the afternoon set for the hold-up, they broke camp, mounted their horses and rode over the mountains until they reached the Globe road. They located a bend in the road where they knew that the stage would have to be slowed down to permit the horses to take the turn. There they took their stand. When they heard the stage coming they started forward on a slow walk to meet it. They pulled out to one side of the road, and when the stage reached them, Boot pulled his .45 Colt's six-shooter and Pearl her .38, and covering the driver, they shouted to him to stop sudden and elevate his hands. The order was promptly obeyed, and while Boot remained mounted, Pearl dismounted and ordered the occupants of the stage to "pile out." Her order was carried out with the utmost haste. Joe told her to search for guns. This she did but found none; but later when she looked into the stage to see if there were any stray passengers hiding therein, she found that two passengers had left their six-shooters inside the stage. She gave Joe one of them, a .44 Colt, and kept the other one, a .45 Colt, for herself. Joe then told her to go ahead and search the passengers. The man who appeared the most scared yielded $390. He shook so badly that he would probably have shook it out of his pockets anyway had he not been relieved of it. The next man, a dude with his hair parted in the middle, assayed $36, a dime and two nickels. The third passenger, a Chinaman, coughed up only five dollars. The stage driver had only a few dollars and they did not take it. They gave each of the three victims a dollar and ordered them to climb aboard the stage and not to look back. Their instructions were carried out, in so far as they could see.

During the balance of the day they rode over the roughest trails their horses could negotiate and at dark they arrived at Cane Springs, but did not stop there to make camp. They passed right on and reached Riverside at about 10 o'clock. They made no stop here but passed quietly through and kept on the same road for about six miles and then turned south toward Benson, where they expected to catch an east-bound train. They camped that night on the east bank of the Gila river and remained there until the next night in order to give their horses a chance to rest up. That night they rode within six miles of Mammoth, and as both were well known there, they had need to be careful, so they hid in the bushes. They saw several wagons pass and many men on horseback, so they decided to change their resting place. Leaving their horses in the brush, they climbed up the side of a big sandstone hill to where there were some small caves and entered one of them. After crawling back about twenty feet, Joe stopped and told Pearl that he could see two bright eyes shining just ahead of him and that he was going to take a shot at them. He fired and then crawled in further and found that he had killed a wild hog which had taken refuge in the cave. The powder smoke made breathing so difficult in the little cave that they backed out nearly to the entrance and stayed there all that day. As soon as it was dark they went to their horses, saddled them and rode back toward Mammoth. Joe slipped into town and obtained some provisions and tobacco without anyone learning his identity. They then passed Mammoth, crossed the river again and rode as far as the school house, and then hid themselves in the brush at the far end of a large field. They secured feed for their horses here and, making a bed of straw and dry grass, they forgot their troubles and slept all night.

This information about their wanderings and dodging about was given to Lorenzo D. Walters, a well known officer of Tucson, who knew Pearl Hart quite well, and she talked freely to him after her capture and while she was in jail at Tucson.

At daylight the next morning they started on their journey to the railroad. After riding about ten miles their horses began to show signs of extreme weariness on account of the very hard riding and having had very little to eat, and Pearl suggested that they turn the horses into someone's pasture and provide themselves with fresh mounts, but Boot said they would not do that, so they rode on. Shortly afterwards they came to a wide ditch, which was full of water. Pearl jumped her horse safely over, but Joe's horse fell short and landed in the water and he nearly lost his life before he could get untangled from his saddle. Finally he got his horse righted and out of the water, but as their horses were both worn out they decided to make camp in order to let them rest and graze while they themselves did some cooking and much needed eating. Rain fell all day and kept them soaking wet.

As soon as it was dark they again started on their journey toward the railroad and rode steadily until 5 o'clock in the morning and again made camp. They had slept about three hours, when they were awakened by shouts and shots. They jumped up and grabbed their guns, but found themselves looking into the muzzles of two unusually large calibred Winchesters, which were held by two members of the sheriff's posse.

They were captured within twenty miles of Benson, and the chances were largely in their favor that they would have made their get-away out of the country had they reached the railroad, as they had plenty of money. They were first taken to Benson and then to Casa Grande on the first west-bound train. From there they were taken to Florence which is the county seat of Pinal county, and in the county where the holdup was staged. On account of the better accommodations for women in the Pima county jail at Tucson, Pearl was transferred to Tucson.

On the day of her transfer to Tucson she tried to commit suicide, but the guards prevented her from carrying out her rash attempt. Pearl stated later that she was sorry that she failed, for she and Joe Boot had sworn never to serve a term in the penitentiary.

One evening when Pearl was served her supper, she hid a case knife and its absence was not noticed by the jailer. That night she loosened and removed sufficient bricks from the double wall of the jail to permit her to escape, but she was soon missed and located walking around town, and was returned to the jail from which she had so recently made her escape. In due time she and Joe Boot were tried and found guilty of robbery by force of firearms, and Boot was sentenced to serve thirty-five years in the penitentiary at Yuma. Pearl drew a five-year sentence and served nearly half of it, when she was pardoned out.

One day, about twenty-five years later, an elderly lady walked into the Pima county jail and asked that she might look the jail over. As such a request was rather unusual, without some explanation, she was asked the reason for her anxiety to look over the jail, and she replied: "I am Pearl Hart, and spent some time here about twenty-five years ago and I would like to see my old cell." She was accorded the privilege of inspecting her old quarters and, after thanking the officer in charge for his courtesy, she departed, no one knowing where to or when.

This data about Pearl Hart was furnished me by Mr. Walters in 1928. He passed away in Tucson, Arizona, March 22, 1943.

The photograph of Pearl Hart on the cover of this issue of Frontier Times comes from the famous Rose Collection of Old Time Photographs. In collaboration with Mr. N. H. Rose of San Antonio, the writer is now arranging to publish a photographic "Album of Gunfighters," which will contain portraits and sketches of nearly all of the outlaws and gunfighters, male and female, of the Old West. The book will contain around 400 actual photographs of these colorful characters.

‹ Back