By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

Over the Goodnight and Loving Trail - Annie Dyer Nunn

[From J. Marvin Hunter’s Frontier Times Magazine, November, 1924]

It was a strange funeral procession, that which followed the Goodnight and Loving trail in 1867 from Fort Sumner, New Mexico, to Weatherford, Texas, a distance of 700 miles. Oliver Loving, the first to find an outlet for Texas cattle, had made his last long drive; and the western frontier with its trackless wildernesses and featureless wastes of prairie would know him no more.

The casket, in which lay the remains of this great pionneer, was carried in a wagon drawn by a mule team. Nine cowboys on horseback rode in front of the wagon and nine behind; these were followed by the chuck wagon and remuda. This escort was the Goodnight and Loving outfit which had delivered 2,500 head of steers into Colorado and now were homeward bound. The sad journey was singularly peaceful; not an Indian was seen during the whole time.

The first trail over which Texas cattle were driven to northern markets was blazed by Mr. Loving in 1859. Beginning in Palo Pinto County, Texas, it extended through the western cross timbers, on through Northwestern Texas and into Colorado as far as Denver.

During the Civil War, Mr. Loving ceased to drive his cattle north, but resumed in 1866. His cattle, during the war, were sold to the Confederates, but they never paid the $150,000 due to him.

In regard to conditions at the close of the Civil War, Emerson Hough says:

"The Civil War stopped almost all plans to market the range cattle, and the close of the war found the vast grazing lands of Texas fairly covered with millions of cattle which had no actual value. They were sorted and branded and herded after a fashion, but neither they nor their increase could be converted into anything but more cattle. The demand for a market became imperative.”

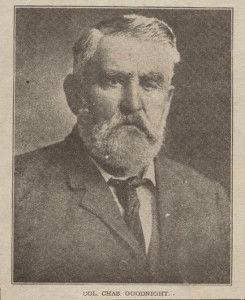

In 1866 Charlie Goodnight, afterward one of the leading cow men of Texas, finding himself with plenty of cattle but no money,determined to push out to northern markets. Oliver Loving declared the project impossible. The Comanches and Kiowas, fierce nomadic tribes were prowling through the western country. Loving pointed out that no trail herd could escape them. Of this Goodnight failed to be convinced, and in the end Loving decided to go with him, taking a herd of his own.

In New Mexico and Colorado there were no cattle. A man was fortunate to be able to rent a milch cow for $5.00 a month. At Fort Sumner, New Mexico, the government was needed. Goodnight and Loving proposed to supply it .

In 1866 they surveyed the Goodnight and Loving trail, perhaps the most famous of all the old cow trails. It hewn in Young County, Texas, and extended southwest to the Pecos River; here it turned northwest, following the course of the river four hundred miles to Fort Sumner and beyond. It then crossed the divide between the Platt and the Arkansas rivers seventy-five miles east of Denver. It ended at the mouth of Crow Creek.

The first part of the trail down to the Pecos was through good country with plenty of grass and water, but along the Pecos it was bleak and forbidding. There was little grass and the only semblance of tree life was the wild mesquite. In speaking of this country Colonel Goodnight recently said. "The Pecos country was the most desolate I had ever explored The river was full of fish, but besides the fish there was scarcely a living thing, not even birds and coyotes." The country was again good along the upper Pecos and in Colorado.

Such was the trail over which Loving made his last drive. The events of this drive deserve a prominent place in the history of West Texas.

Loving and Goodnight had now entered partnership—an ideal one, since Loving knew the trail and its ways, and Goodnight knew men and cattle. Both were men of high honor and courage. Loving was fifty-five years old; Goodnight thirtyfive.

It was in June, 1867. The outfit consisted of twenty-five hundred head of steers and eighteen men. From the first the Indians were a constant menace. They attacked the outfit at the fork of the Brazos River, stampeding the herd and wounding one of the men. On the lower Pecos they again attacked and succeeded in getting away with three hundred and sixty head. An unsuccessful attempt was made to recover them.

The outfit had gone one hundred and fifty miles up tee Pecos when Mr. Loving having seen no further signs of Indians, decided to take one of the men and ride on ahead to secure the government contract for furnishing beef to New Mexico, which was to be let at Santa Fe. His partner did his best to dissuade him from this perilous venture, for two lone men would have little chance against the Indians, who might surprise them at any time. But Loving was determined. He asked Bill Wilson, a trailsman, who having but a few head of cattle attached them to tile large herd, to go with him. Wilson agreed. Loving could not have selected a better man, for Wilson was a brave and genial man.

Known as One-Armed Bill Wilson. who was with Oliver Loving at the time Loving was wounded. Bill Wilson gave the editor of Frontier Times an account of this fight which coincides with the story here given. Bill Wilson was in San Antonio in 1930. He died in 1923.

Promising Goodnight that they would travel entirely by night, resting and hiding in the daytime, they set forth. They rode good horses and each man was armed with two pistols and a rifle. They had traveled but two nights when they grew weary of these arrangements. especially as there were no signs of Indians; so, throwing caution to the winds, they continued the journey by daylight.

They had immediate cause to regret this decision, however, for on the afternoon of the first day they saw a large band of Indians loitering across the plain to the south of them, apparently shooting prairie dogs. The white men left the trail and dashed toward the breaks of the river, their only hope of protection . Even as they started the savages gave pursuit . A mad race followed but the white men reached the river first. They tied their horses to some bushes and ran behind a sand dune on the bank of the river and into a spot which offered good protection. They had barely done so when about six hundred Comanches swarmed into the breaks.

A small arroya had cut a notch eight or ten feet from the edge of the water to the sand dune, the men were safe from the arrows of the redskins. There was only one direction from which they could be reached and that was from across the river; but their guns kept this space clear They were further fortified.by a bend of the river above them and one below them. The Indians, perceiving that they could not reach the men without imminent danger to themselves, asked fora parley, and the men decided to grant it. It was arranged that Wilson, who could understand the Indians, should go out and talk to them while Loving stood guard to keep any who might be lurking in the brush on the river's bank from shooting his comrade in the back . The two men were several yards from their hiding place when Wilson thought he heard the snapping of a twig.

There's an Indian in that brush now," he warned.

“No, there isn't," Loving replied. “You are just scared." As he said this he started toward the bushes. Across his left arm he had a holster with two pistols which he had been carrying over his saddle horn.

The main body of Indians was about 150, yards away at the foot of the sand dune. Wilson kept a keen eye on the bushes which Loving was approaching; for he knew that if there was a demonstration from that direction, the other Indians would charge. Loving had gone about twenty yards when an Indian rose from behind the bush and leveled his gun at Loving. Wilson's shot shattered the silence simultaneously with that of the Indian. The Indian dropped behind the bush and Loving staggered toward Wilson.

"I'm killed," he gasped. "Take my gun and do the best you can with it."

At that moment Wilson saw the Indians from the foot of the hill charging them. He emptied his own gun on them; then seized Loving's and emptied it. The savages were repulsed and the white man again got to cover.

As Wilson lay beside Loving waiting tensely for anything that might happen, he observed a slight movement of some tall weeds a few feet away. He knew that an Indian vvas creeping through them, parting them with his lance as he advanced. The Indian came nearer and nearer. He was about to poke his head from the weeds, when a huge rattlesnake roused up right in front of him.

The reptile gave a loud warning and then glided off in the opposite direction which was toward Wilson. To his unspeakable horror it came to his side and quite chumily coiled itself. His life now hang by a thread. If he fired at the Indian, who he knew, was even now leveling his gun at him, the noise would cause the snake to strike; but Wilson feared the snake more than he did the Indian so he remained perfectly still. The Indian tanked from the uncanny scene evidently frightened by the performance of the snake, for this was the sort of thing which aroused the superstition of the old-time redskins. Wilson remained rigidly still and presently the snake glided into the bushes.

About dark the Indians led the horses away and with them went all the provisions possesed by the trailmen. Night came on and their perilous vigil continued. What must have been Loving's thoughts in those terrible hours, as he lay facing death, separated from his friends by hundreds of miles

Believing that he could not last til morning, he insisted on Wilson's trying to escape before it was too late. Wilson decided to make the attempt.

"Tell Goodnight to get word to my family, telling them how and where I died," said Loving. If I can, I will keep the Indians off until he gets here; but if I see that they are about to take me, I will commit suicide to escape their torture."

Wilson consented. When the moon went down, shortly after midnight, he divested himself of all of his clothes except his undergarments and slipped into the river. Across his shoulder was one of Loving's guns, the only one in their outfit that fired a metallic cartridge. Loving had forced this gun upon him knowing that the others would not shoot after being in the water, and his only hope was to swim down the river, but he was so handicapped with the gun that he almost drowned. Seeing that it was impossible to carry it any farther, Wilson left it sticking in the sand under the water where the Indians would not be apt to find it.

A hundred yards down stream he knew that he was surrounded by them, but they had not discovered his presence. One sat on horseback in the middle of the stream, splashing his foot in the water. So absorbed was he in this play that he did not see the white man. who, a few feet from him, was drifting by in the shadow of the smart weeds which drooped over the edge of the bank.

Farther down siream Wilson left the river and set out across country in th e direction of the herd. The sandy soil seemed barren of growth save that of every variety of sand bur. These brought exquisite torture to the barefooted traveler . There followed a never-to-be-forgotten march of three days. Faint from hunger, going hours without water, for at times he was far from the curving river, he trudged on in the blistering heat of a July sun, which parched the bur-strewn sand beneath his bleeding feet. The second day he found the end of a tepee pole and this he used as a cane.

By the third night he was almost exhausted, and barely able to drag one lacerated foot after the other. To add to his discouraging situation, a pack of wolves began to follow him. He was afraid to sleep because of them. Their skulking forms were ever near, and all of Wilson 's efforts to drive them away proved unavailable. No better idea of his plight can be gained than from his ow n words: "I would give out, just like a horse, lie down and drop off to sleep. When I woke up the wolves would be all around me, snapping and snarling. I would then take the tepee pole and drive them away, but when I resumed my journey they would drop in behind me. I kept this up until daylight, when they left me."

He struggled on until noon, when he reached a hill which he felt sure the herd of cattle would pass. Barely able to move he crept into a sort of cave which had been whipped out by the play of the wind. In this he was protected from the burning sun. In a few hours the herd arrived, and Wilson staggered out of the cave. "He was the most terrible object I ever saw," Colonel Goodnight relates. "His underwear was stained with mud, his tongue was swollen by thirst, his eyes were wild and bloodshot; and every step he took he left blood in the track."

Goodnight made immediate preparations to go to Loving's rescue. With six good men, mounted on the best trail horses he set out. All that night it rained torrents and it was so dark at times that the party was forced to halt until a streak of lightning would momentarily light the way. At four o'clock in the afternoon, they reached the place where Wilson said that he and Loving had left the trail.

On a mesquite bush close at hand was a small piece of paper pinned to a thorn. This was recognized as a leaf from Loving's notebook which he always carried in his saddlebag. On it was a drawing —a bit of Indian cynicism—of an Indian and a white man shaking hands. Oddly enough, the white man was wearing a silk hat, a thing at that time unknown in West Texas.

About two hundred yards north of the trail the party discovered the tracks of Loving and Wilson whereupon they dashed across the prairie toward the river. The silent hills gave no clue to what had occurred. It was evident, however, that the Indians had been gone but a short time, for the bank of the river was still wet in places where they had climbed out of the stream. It looked as if they had not found Loving.

One afternoon, two weeks later, when the Goodnight and Loving herd was within seventy-five miles of Fort Sumner, Goodnight was riding ahead to see whether there were Indians in the vicinity when he saw a man riding towards him. Believing him to be an Indian, he maneuvered around a hill, keeping out of his sight, and came up behind him. Then he recognized him as a white man named Burleson, who had a herd just behind.

Goodnight informed him of Loving's death.

"Why, Loving is not dead!" Burleson replied. "He is at Fort Sumner, recovering from his wounds. He sent word to you to leave the herd and come to him."

All that night the faithful friend rode toward Fort Sumner and arrived there the next morning, making the distance of seventy-five miles in fourteen hours. He found Loving walking about with his arm in a sling and feeling confident of recovery. But his friend was apprehensive after examining his wounds.

The next morning after Wilson's departure, Loving discovered that he was much better. The wound in his side, which he had thought fatal, was not really serious. Meantime the Indians continued to deluge the ravine with arrows and stones, none of which reached him. They dug tunnels through the sand dune to within five feet of where he lay; but they dared not put their heads over the bank to get an accurate shot at him. Repeated attempts were made to reach him from across the river, but after losing two of their men, they desisted. Two days and nights they kept him in the ravine. Then he escaped by way of the river,

Since the herd had had ample time to arrive and had not done so (this delay was due to the outfit's having halted to rest the cattle), Loving decided it had been captured by the Indians. So instead of going down the river to meet the cattle he went up it to a crossing in the faint hope that some passer-by might find him. He reached the crossing two miles up stream. Here a clump of chinaberries grew; and under these he lay, ill and exhausted. His water-soaked gun would not shoot; otherwise he could have killed some birds for food. Many long hours passed with Loving growing constantly weaker; and with no cessation of his intense pain. The only way he could get water to drink was by dipping his handkerchief, which he had tied to a stick, into the stream two feet below. Three days and nights went by in this manner, when at last his indomitable courage failed him, and he was overcome by a heavy stupor.

At noon the third day he was aroused by someone standing over him. When he became thoroughly awake he saw that the newcomer was a white boy. He was a German traveling from Fort Sumner with three Mexicans. He had come upon Loving while looking for firewood.

Loving was taken to the covered wagon, where the Mexicans fed him corn-meal gruel. For $250 Loving hired the men to return with him to Fort Sumner.

When they were fifty miles from that place, they met Burleson, who was riding out for news of his herd. Upon being informed of the situation, he rode back to town as fast as his horse could carry him. Sending the government ambulance and doctor to take care of the sick man. Loving lived for some days after reaching Fort Sumner: but the care his wounds received was not of the best and blood poisoning resulted. "So passed as good a man as ever lived," in the words of Bill Wilson.

‹ Back