By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

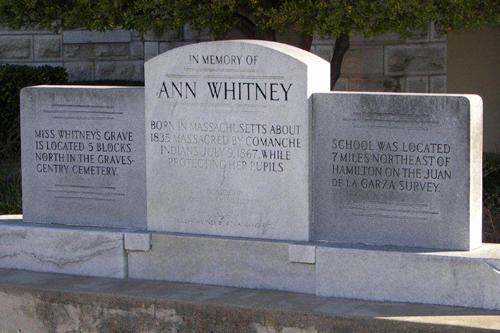

MISS ANN WHITNEY, THE FRONTIER HEROINE

From J. Marvin Hunter’s Frontier Times Magazine, July, 1927

THE SCHOOL children of Hamilton county have marked the last resting place of Ann Whitney, frontier school teacher, who was murdered by the Comanche Indians, with a monument commemorating her heroism in giving her life to save the children of the Warlene Valley school. Each year the children of Hamilton county pay tribute to this frontier teacher by caring for the grave and placing flowers around the monument erected to her memory.

At 1 p. m. Thursday, July 11, 1867, Ann Whitney rang her bell to call the children from their play into the little log schoolhouse on the brink of the Leon river, overlooking the beautiful Warlene valley. An hour later the daughter of Alex Powers, while standing at the door of the schoolroom, saw a number of men whom she took to be Indians, coming down the valley. Miss Whitney insisted that the men must be cowmen from a nearby ranch who were expected by the school that day, and insisted that all children take their seats.

The Powers girl was not satisfied, and between the logs of the school building continued to peep through the cracks until she was quite sure the men were Indians. Then she sprang from her seat, took her little brother by the hand and crawled through the back window to escape. By this time the Indians had reached a tree some 300 yards in front of the school house where Miss Whitney's saddle horse was tied, and had stopped as though they merely wanted to steal the horse.

Miss Whitney closed the door and bade the children escape through the window and into the brush in the river bed below. All of the children succeeded in getting through the window and into the brush or under the house except Lewis Manning and his little sister, who was sick, and John Kuykendall and his sister. In a few minutes the Indians had surrounded the log house and one of their number, a red-headed man, spoke up in English, “Damn you, we have you now!"

Although she read her fate in the bloodthirsty eyes and hideous, painted faces of these savages, Ann Whitney did not lose her presence of mind. While the murderous gang had their arrows aimed at this heroic woman awaiting orders to shoot, she was pleading with them to kill her, but to let the children alone. The first volley of arrows fired through the cracks of the logs of the house filled her body with wounds, but she kept walking from one side of the house to the other pleading with the Indians to save her school children. Failing in their attempts to bring their victim to an end by shooting through the cracks of the building, all of the Indians gathered around the door of the house to force an entry into the building; and while they were thus engaged, Ann Whitney mustered the last ounce of her fast failing strength in helping the two girls out the back window and getting the boys under the house through a loose plank in the floor. When the Indians battered the door down and entered the building, Ann Whitney's body obstructed the doorway, but her spirit had gone on to the home of heroes and heroines.

One of the Indians stepped on the loose plank in the floor, raised the plank and dragged out John Kuykendall and Lewis Manning. The red-headed leader asked the boys if they wanted to go with them, whereupon John Kuykendall, through fright, said he did, but Lewis Manning told him "No!" The leader, angered by Lewis Manning's reply, cursed him and stripped him of his clothes, including a new pair of red-top boots that Lewis had been displaying so vainly since his return from town the previous Saturday. As the clothes were all removed, Lewis dashed out the door to safety in the river bed, with an Indian pursuing for a short distance.

Aside from the scare, which his pals claim turned his hair white (a thing Lewis will not admit), Lewis Manning was none the worse for the experience, and remains alive today at his home in Fort Worth.

A few minutes later, Miss Amanda Howard and her sister-in-law rode into the valley. They saw two men riding to meet them as they neared the school, and perceived that the men were Indians. Miss Howard, riding a wild horse, had some difficulty getting her mount turned from his course and was almost caught before she succeeded under whip and lash in getting the horse in a run toward the Bagget home a mile away.

_____________________________________

_____________________________________

Approaching the fence to the Bagget ranch with the Indians in hot pursuit, Miss Howard saw that her only hope of escape was in forcing her horse to jump the fence, which he did in one clear leap. Her sister-in-law, however, did not succeed so well, but, being thrown across the fence as the horse suddenly stopped, made her way to the house in safety.

Miss Howard immediately began making plans to notify the settlers across the river of the presence of the Indians at the school. To reach the settlements it was necessary for her to gain access to a crossing near the school building, from which the Indians might easily cut her off. But no time was to be lost in taking into consideration any personal danger; with grim determination she reined her half-wild mount in the direction of the crossing on the river; the Indians saw her and with blood-curdling yells dashed forward, bent on staying her course. By ten rods this young heroine of 17 years succeeded in gaining the crossing and was soon in the settlements.

The Comanches immediately made their way out of the valley, taking John Kuykendall with them. On their way out they met a Mr. Stanigline and family, killed Stangline and shot his wife, but she recovered.

Amanda Howard soon notified all of the families in the settlements, and by nightfall a posse was formed to follow the Indians, but abandoned the chase after a pursuit of 100 miles.

Two years after the above incident, the mother of Tom C. Pierson, present tax assessor of Hamilton county, and of J. O. W. Pierson, who led the posse in pursuit of the Indians, saw advertised for sale a boy who had been bought from Indians in Kansas. From the description given, Mrs. Pierson felt sure the boy was John Kuykendall and so notified the Kuykendall family. Isaac Kuykendall, brother of John, made his way to Kansas, found his brother, paid the purchase price and returned home.

John had forgotten his name, and had almost forgotten the English language, but he recognized his brother and the family on his return home. He told of the hardships he endured when the Indians carried him away, how they kept his feet tied under a horse for several days, how he suffered from hunger, and how he was brought food by the red-headed man just before he was completely exhausted. The posse in pursuit of the Indians was seen by John at one time, whereupon the Indians scattered, leaving him with one Indian, who led his horse for several days

352 complete issue FLASH DRIVE, for only $89.95.

You'll have all the stories you could ever read! Click here!

‹ Back

Comments