By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

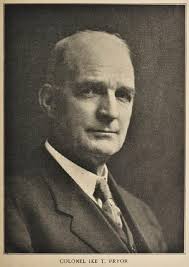

IKE T. PRYOR WAS A GREAT CATTLEMAN

J. Marvin Hunter, Sr.

[From Hunter's Frontier Times Magazine - March, 1949}

Colonel Ike T. Pryor, who died in San Antonio in 1937, was one of the outstanding cattlemen and trail drivers of Texas in the 1870s and 1880s. His life story read like a romance, for it was made up of thrills and pathos, struggles and hardships, failures and triumphs that befell but few men who successfully overcame such obstacles that he met and conquered. A pioneer of the days of the of the unfenced range, he became one of the most widely known cattlemen of America, and if his reminiscences had ever been written they would afford a complete panorama of the cattle industry of the United States. From the early days of the grass trails, when the great herds of Texas longhorns were driven thousands of miles to market, down to the time when bred cattle, modern marketing systems and rail transportation, he had been an active participant.

Born at Tampa, Florida, in 1852, he was left fatherless at the age of three years. Shortly after his father's death, his mother took her family to Alabama, where two years later she passed away, and he was taken in charge by his uncle at Spring Hill, Tennessee. At the age of nine years he ran away from the home of his relatives and boldly struck out into the world for himself. This was in 1861, with the Civil War just beginning its devastating reign. Attaching himself as a newsboy to the Army of the Cumberland, he lived among the hardships of the campaign, and witnessed the scenes enacted at Murfreesboro, Chickamauga, Lookout Mountain, and other desperately fought actions of the war between the states. It was in such environment that tried the very souls of men, that an impressionable boy not yet in his teens had the early moulding of his character, and in it was seasoned the courage that had sent him, inexperienced and frail, to challenge for life and fortune.

It was my privilege to know Colonel Pryor intimately in his later years, and he related to me many of his thrilling experiences. He told me that he came to Texas in 1870 and started work as a farm hand at $15 per month. The next year he entered the cattle industry, as a trail hand, driving a herd to Coffeyville, Kansas. From then on his activities for many years were uninterrupted in the driving and marketing of livestock as practiced in those years. In 1873 he was employed on the Charles Lehmberg ranch in Mason county, and there he really began his upward climb in the cattle business.

I personally knew many of the men with whom he was associated in Mason and Llano counties, among them John W. Gamel, Major Seth Maberry, Ship Martin, and others. In the October, 1945 issue of The Cattleman, published at Fort Worth, Texas, there appeared a splendid article, written by Ruth Hunnicutt, reciting some of the experiences of Jack Jones, an old-hand, 82 years old, who was still (1945) living in Austin, and still managing his stock farm south of the Capital City. Mr. Jones relates facts that so vividly portray the fine upstanding character of Col. Ike Pryor, that I am taking the liberty to quote much of Miss Hunnicutt's articles. Said Mr. Jones:

"I've lived here all my life—and that's been a long time—and I've seen all kinds of changes come to Austin. I can recollect then Ike T. Pryor furnished Austin with meat. Ike was in partners with Ship Martin then. Ship didn't own no land—he was just squatting up in Llano county—but he owned a bunch of cattle. Ike went in business with Ship on credit—took a half interest in a thousand head. They used to drive about twenty head to Austin once a month. Wasn't no stock yards then, they held the cattle down there on the south side of the Colorado. All the butchers in town knew that regardless of the weather, Ike would be there on the first day of each month with some good fat cows. Llano was the only country where you could get fat cows the year around.

"Ike got rich in the cow business. Folks started calling him Colonel Ike after he got older. I never did know where or why he became a colonel but he told me one time why he became a cowman. He said he was plowing in a stump patch, drawing $15 a month wages when a fellow said to him, 'Ike, why don't you go in the cow business? All you have to do is just pick you out a brand and go to work putting the brand on mavericks. Pretty soon you'll grow a nice herd.' Well.

"I expect Ike owned as many cows as any man in Texas in 1884. That was the year I went up the trail for him. He had 45,000 head in different herds scattered around over the Brady prairie that year. Jeff Farr was my trail boss. We were driving a herd to Colorado. There were three other herds pretty close to us. One night the worst storm I've ever seen hit us. Lightning just danced from one pair of horns to another throughout the whole herd. Course the cattle got scared—they tried to break several times but we held them, the best part of them, anyway. Guess maybe we lost around five hundred head but we kept the herd together.

"The next morning Ike comes riding out. He was driving a double buggy. The first thing he says when he steps out is, 'Got anything to eat, boys? I ain't had no breakfast.'

"Soon as he gets a cup of coffee in his hand he says, 'I didn't sleep none last night—worrying about you boys all out here in the storm.' Ike was staying in Brady at the hotel.

"He sure looked pleased when he saw the herd was still together. 'I done been to the other camps, Jeff,' he says to the boss. 'They didn't hold their herds.'

"After he ate his breakfast he left us. When he started off he says, 'Jeff, you got some good boys—be good to them. Feed them well and take good care of them—they're real cowboys.'

"We went from Brady to Dodge City and went over to Colorado. Never saw a living soul on that last 150 miles of the trip. Bue we saw plenty of Indians on the trail up to Dodge City. They was friendly Indians, though, didn't give us no trouble. Jeff gave each chief a beef or two as we went through their territory. And we always fed the Indians that came out to meet us. They didn't eat with us—they sat off watching us, then when we finished, the cook would call them over. They'd eat everything in sight. They was particularly fond of biscuits. What those Indians liked most of all was chewing tobacco. We soon learned not to hand them the whole plug but to cut them off a piece. If you handed them your whole plug they'd grunt and take off with all your tobacco.

"Our horseler, the fellow who wrangled our horses, told us he saw some Indians kill a beef we had given them. Said they drove it off a little ways from the herd, ran up and knifed it down and ripped it open. He said those Indians fought over the guts. Said they hopped around like a bunch of buzzards, gobbling down those entrials. I didn't see that myself—didn't want to see it, either.

"We had a nigger cook. All of Ike's crews had nigger cooks. Jeff said Ike fed better than the other trail men. I guess he did, we had plenty of good grub. We had dried fruit, canned stuff and plenty of fresh meat. You know, it was the custom to pick up your eating meat. You couldn't eat trail stuff—would give you a fever. That's the honest truth. Jeff always rustled the eating meat. Wouldn't let no other man in our outfit do that job, either. Said that was his responsibility.

"Ike's cattle was branded a J turned backwards behind the left shoulder. That was the trail brand of the bunch we was driving. You see, there was inspectors at the Red River where we crossed into the Indian territory and they looked through the herd and cut back the stuff that did not have the trail brand. Don't reckon they ever had to turn back much stuff. It certainly wasn't no particular big job to stop and brand the strays that fell in with a herd.

"We had about 85 head of horses in our outfit. They was Spanish ponies, all of them come from down around the border—cost about 20 a head I reckon. They was plenty rough, too. About twenty head of them was just plumb outlaws. Never had had a saddle on them—or at least one that stayed on them for any length of time.

"When we got to Colorado we branded out 3,957 head and turned them over to the three Batey brothers from Tennessee. It was their first bunch of cattle. They paid Ike $15 a head for the cattle delivered. The whole herd was yearling steers. The Batey brothers was planning to fatten them and send them north to market. We sold them the wagons, saddles, horses and all. Took us five whole days to brand out that bunch of stock. We was branding in three different pens at once. There was twenty-five irons at a time heating in the fire. The Batey brothers stood over that fire all five days, handing out the hot irons. They did the hardest work of all.

"Texas really looked good to me when we got home. We came back on the train, a much better way of traveling, I decided.

"The next year after I had been up the trail I was down in the Iron Front saloon one day when Johnny Blocker came up to me. Mr. Blocker was a big, handsome man and much of a cowman. I guess he could rope better than anybody in the world. I remember that he was wearing a big heavy watch chain across his front with a gold steer hanging on it. He'd made lots of money with cattle—he loved them. Anyway, he smiles at me and he says: `Jack, didn't you go up the trail for Ike Pryor last year?'

"Then he asked me how much Mr. Pryor paid me. I told him and he says, `Well, Jack, I'll pay you $45 to go up with me. You've had experience and you are worth more money now.'

"I didn't say anything for a minute and Mr. Blocker says, `Will you think it over Jack? '

"Well, I did think it over. But it didn't take me long to do my thinking. I just thought for a minute or two then I said, `No, thank you, Mr. Blocker. I appreciate your offer but I got enough of the trail on my first trip.'

"I reckon it was twenty-five years later when I saw Ike Pryor. I was in the American National Bank; it was in the Driskill Hotel then. Littlefield owned the whole business. I looked over and there sat Ike Pryor talking to Gue Roe. Ike's coal black hair had turned to gray. I was staring at him when he turned his black eyes toward me: He looked puzzled for a minute, when he smiled and then he said, `Wait,' ain't this Jack Jones?' He stopped his conversation for a minute or so and asked, `How's all your folks, Jack?' I told him, and asked about Jeff Farr, my old trail boss.

"Ike turned to Roe and he says, `I made a real man out of Jeff Farr. He was an Austin boy. Just a big, ignorant kid running around on the streets when I picked him up. Asked his folks to let me take him to Llano with me and make a man of him. Told them he wouldn't learn nothing but meanness just growing up in idleness.'

"I reckon Mr. Pryor did what he said about Jeff, alright, because he said the last time he heard from Jeff he was ranching up in Colorado, where he owned a fine string of cattle and where he'd been sheriff for eight years. That was the last time I ever saw Ike T. Pryor. He was a great cowman and a good fellow."

**********

352 issues – Hunter’s Frontier Times Magazine Flash Drive!

‹ Back