By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

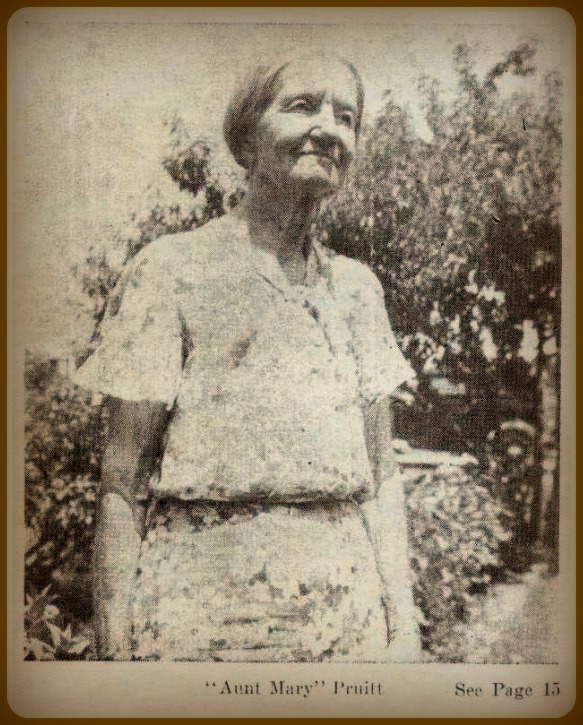

"AUNT MARY" PRUITT - By T.U. Taylor, Austin, Texas

[From J. Marvin Hunter’s Frontier Times Magazine, October, 1940]

There is a legend to the effect that if a person gets a drink of Blanco water, such person will never be content at any other place under the sun, but will always have a desire to again quaff the waters of the Blanco river. This was long before the dams converted the clear rippling waters into muddy pools that add nothing to the beauty or utility of the landscape.

Into this region came Uncle Clem Hinds in the early fifties, bringing his wife and two or three children. His wife was the winsome Kate McCoy of Gonzales county, who was born in Texas in 1823. The Hinds came with Captain James H. Callahan and his family, and while Capt. Callahan was on the frontier scouting and fighting the Comanches, Uncle Clem Hinds did yoeman service for the valley of the Blanco. The first house occupied by the Hinds family was a rather rude log structure, but the next was constructed by Uncle Clem from native stone. This was rather an ambitious house for the times and there it is until this good day of the year 1940, on the north bank of the Blanco, about one and one half miles west from the old court house. In this stone house in the year 1859 was born Mary Hinds, now hale and hearty at the age of 81, a store-house of the history of Blanco county and its people. When she first noticed that her father, Uncle Clem Hinds, had an old wound in the shoulder, she was then told of the deadly fight, when her father went on a peaceful mission with his friend, Captain Callahan, and saw his friend shot to death and his other friend, Maulheel Johnson killed almost instantly by a blast from the Blassingame guns. Her father, though severely wounded, reached his home, was helped to his bed by the timely service of J. M. Watson, and finally recovered to help upbuild the new county of Blanco. Captain Callahan and Maulheel Johnson were slain before the county of Blanco was created. (The term "Maulheel" was applied to W. S. Johnson on account of the fact that one of his heels was abnormally large, and in looking at it from the rear it had the appearance of an old hickory maul that the pioneers used to split rails. Some jokester started the name of "Maulheel," and old settlers recall "Maulheel" Johnson, but not W. S. Johnson.)

"Aunt Mary" recalls the early times, some events of the Civil War, and many events of Indian raids, and Indian scares. While she never saw a live wild Indian, she saw their tracks in the yard the next morning after the red men had walked around the houses and barns in search of horses. Horses with the red men were staple and ready cash.

Uncle Clem hinds and his wife Kate McCoy Hinds replenished the earth with twelve children as follows:

William Hinds born in 1848, never married, and died at the age of 21.

James Clements Hinds married Colvin Pruitt.

Ellen Hinds married first Ben Hinds and second, John Hinds.

Kate Hinds, married Robert Kelley.

Susan Hinds, married Jasper Cloud.

Nancy Hinds, married first Perry Bay; second Henry Lawson, her brother-in-law; third, Elijah C. Pruitt, another brother-in-law.

John B. Hinds, married Emma Ferguson.

Minerva Hinds died young.

Laura Hinds, died young.

Alice Hinds, married Elijah C. Pruitt.

The reader will notice that "Aunt Mary" Pruitt has been married three times, and twice she married brother-in-laws, and her present husband, Elijah C. Pruitt (known in Blanco as "Lige" Pruitt, is still living and on July 4, 1940, "Aunt Mary" had all eleven of her living children at a family reunion, and a big turkey dinner was served in the yard of the home on an improvised table.

Thrice has the writer in the month of July talked to Aunt Mary about her early life, early times, early schools, etc. The stone house in which she was born is still standing within a stone's throw of the Blanco river. She recalls the large fireplace, with the old back log, and how the family had to guard against getting out of fire. Each night after supper in the big room the live coals and embers were covered with ashes, and the next morning all you had to do was to uncover the embers, and place a few dry sticks and in the twinkling of an eye you had a sparkling fire that soon warmed the room and cooked the breakfast. However in spite of all care, sometimes on rare occasions the Hinds family ran out of fire, and then the skill of the frontiersmen came into play. If your shotgun was ready all you had to do was to load it with powder, with a little wadding, but no bullets or blue whistlers, and then shoot into some cotton or shoot into a punk or spunk or a rotten stump. The powder would ignite the tinder, and you could soon coax it into a blaze. The writer saw a skillet lid used with cotton, powder and an old file produced a spark that soon had a fire going.

The cooking was all done on the old fireplace with the skillet, frying pan, old baker, or what was later called a dutch oven, but many called it the "baker." The old boiling pot that hung from the iron rod across the big grate served many purposes. Into this pot would be placed some greens, a piece of bog jowl, some seasoning, and then the fire underneath did its work like no modern domestic science can dream of. When it was all done, the greens and jowl were taken out of the pot, and in the bottom of the pot was left a half gallon of that delicious concoction known from the Red River to the Rio Grande as "potlicker." The writer cannot think of this delectable soup, or drink it without his mouth watering. "Aunt Mary" helped her mother, Kitty McCoy, cook biscuits on the open fireplace and for years there was not a cook stove in Blanco county, and it was an event when the first one arrived at the Hinds' home.

All the wool was saved and preserved, and then in the fall came the time to card the wool into rolls, lay these away to be spun into thread later by the old spinning wheel. There was the old loom in the Hinds' home and early did young Mary learn to pace up and down and make the spinning wheel sing its song of peace and home.

And Mary had to help her mother and sisters with the loom that took the woolen yarn and converted it into the linsey woolsey for the dresses of the girls, and into the homespun for the coarse breeches of the father and the brothers. This linsey woolsey was not all drab and drear. "Aunt Mary" was soon taught to use certain barks, especially walnut, color the cloth, and she can remember to this good day some seventy-five years ago when she got her first dyed or colored linsey woolsey skirt. And then Uncle Clem went to San Antonio or Austin just after the war and brought homered spotted calico, and Mary, at the age of seven or eight, got her red spotted store calico dress. She remarked recently at the age of 81:

"No queen or princess ever strutted like I did when I looked at myself in the looking glass that day. No peacock in Blanco county was as proud as I was."

"Aunt Mary" recalls that they always bought their coffee in the green berry state. They parched their own coffee, and a hungry man can smell this parched coffee a half a mile away. They never heard of coffee that was already parched, and as for ground coffee, it would not have been tolerated. The coffee mill was nailed or attached to the wall, and the coffee was ground fresh for each meal. It needed no radio hired to proclaim its virtues. It was fresh; it was pure; it was dated that very meal. It needed no foghorn to proclaim its goodness or its excellence.

We milked in the old pig pen, and strained the milk, and churned in the old dasher churn.

The hardest job "Aunt Mary" tackled as a girl was not the spinning wheel, making linsey woolsey dresses, but in a certain operation in knitting socks and stockings. She soon caught on to the knitting from the toe of the sock, expanding to the size of the foot, and then proceeding to the instep, and finally she arrived at the point when there appeared a turn in the road, and a certain heel had to be rounded out or passed around and then came that often heart-breaking operation of "turning the heel" of the sock. The writer has seen his own sisters weep over the "turning of the heel." But all it took was a few instructions from such mothers as Kitty McCoy Hinds to conquer this hard job of a girl's pioneer life.

The dresses, coats, and breeches, were all made by hand until that labor-saving machine known as the "sewing machine" came into West Texas. It seems that the Wheeler & Wilson sewing machine was the pioneer relief in the years that followed the Civil war.

"Aunt Mary" finally was old enough to go to her first school and her first book was Webster's Blue-back Speller, in which she learned to read and spell. Her first teacher was John B. Tennyson of Blanco county. She used no blackboard, but the slate and slate pencil. When she wanted to rub out her work on the slate she did not hesitate to dampen her fingers with spit and rub it with her fingers, if she did not have a rag. It was a one room log house, no glass windows, but a section of one log was sawed in two and it was left open. The seats were made of split logs, and had no backs.

The first light they used that "Aunt Mary" recalls was the ordinary dip with its plaited wick, and then came tallow candles. Modern conveniences reached their very pinnacle when Uncle Clem brought home from San Antonio an oil lamp which was nothing but the enlarged modern oil can. It was about three inches in diameter at the base, and it tapered to nearly a point at the top, being conical in shape. Uncle Clem Hinds invited some friends in and he proceeded to show off his new lamp. He cautioned them about its danger. All the company sat down at the table, and the children had to wait for the second table, but they were permitted to peep in the doors and see the new exhibition of public utilities. Uncle Clem proceeded to light the new lamp in the presence of all his company, with all of his children peeping through the doors. It worked like a charm. It was nothing but the old tallow dip with kerosene substituted for the grease. The dinner was concluded and the table was set for the children, and their hearts were fixed on eating by the new lamp. To their consternation Uncle Clem came into the room, sat the tallow candle on the table, and solemnly took the new lamp into the big room where his guests were sitting. The children were sorely disappointed. Later the children went to school to W. H. Bruce.

John W. Speer arrived in Blanco in 1859, and in 1862 Judge Gates appointed him county clerk to serve for thirty days till a special election could be held, and at the special election he was elected for the regular term. In August 1864 he was again elected county clerk. In 1865 all the county officers were turned out by the federal officers and a new set was appointed. But in 1866 the voters came back and elected John W. Speer county Clerk, and in addition he was appointed assistant district clerk. In 1883 Mr. Speer took great interest in organizing the schools of Blanco and it was due to him largely that W. H. Bruce came to Blanco in 1884. Mr. and Mrs. John W. Speer raised a large family and his descendants are carrying on the old time Texas spirit in Blanco and other counties. They had the following issue: Joseph; John; Maggie; Mary, Martha, Harry, Thomas and James.

To John W. Speer posterity and civilization are indebted for writing a brief history of Blanco County in the shape of letters to the local newspapers of Blanco. Copies of these have been preserved for posterity.

______________________________________

How about 20,000+ pages (352 issues) of Texas history like the one you just read?

Texas history, written by those who lived it! Searchable flash drive or DVD here

______________________________________

‹ Back