By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

An Old Time Texan Tells His Story

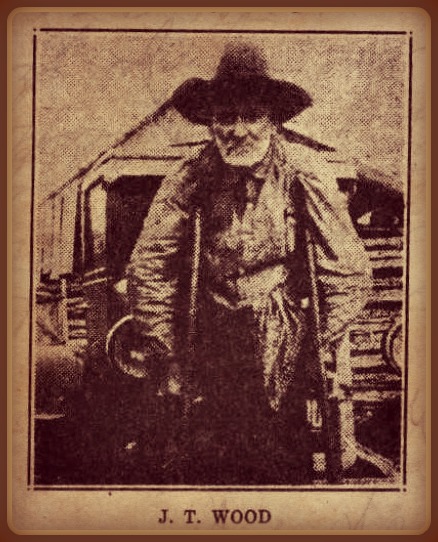

Written - by J. T. Wood, Parksdale, Texas

From J. Marvin Hunter's Frontier Times Magazine, April, 1929]

I was raised on the frontier of Texas, and know all about the privations and hardships of the early settlers of grand old Texas. I was born in San Saba county, Texas, January 6, 1857, and lived there until I was twenty-one years old. My father was among the early settlers of that county. I have been told by some of my relatives that my sister, two years older than my self, was the first white child born in San Saba county. My grandfather settled on a little creek known as Richland Creek. He had a large family and owned several negro slaves. His children all married and settled up and down Richland Creek, and when his grandchildren came to visit him they made quite a crowd of little folks. He would get us all together and take us fishing and plum hunting, and we would all have a fine time. He seemed to enjoy it just as much as any of us. I thought there was no one on earth like my grandfather. When he was with us we never thought of Indians molesting us, although they came into the country every light moon and stole horses and often killed white settlers. I remember being at grandfather's once when I was just a boy, and was playing with the children, when we heard someone hollering away off. Being small, we didn't pay much attention to it. We just played on, and about ten o'clock that morning someone came and told us that the Indians had killed old man Beardy Hall out about the Round Mountain that morning. He had gone out there to see about some sows and little pigs. I suppose he was feeding them to gentle the pigs. This little round mountain was about half way between Richland Creek and the San Saba river. One could get on this mountain and see in every direction for a long distance, so I suppose these Indians were on the mountain trying to locate some horses, when they saw Mr. Hall, slipped up on him and murdered him. Of course they took his scalp with them so they could have their big war dance, as that was their custom when they killed anyone. Since my grandfather died when I was very small, I can only relate some of the experiences my grandmother told me about her life on the frontier. Everyone called her "Aunt Betsy" and grandfather "Uncle Jimmie." She said after the Runaway Scrape they were broke up, so Grandpa cleared up a little field, cut poles, made rails and carried them on his shoulder to fence it, and dug up the land with a hoe. He planted a crop of corn for bread, and of course it wasn't much trouble to kill deer and turkey for meat, but they didn't have much fat about them. Grandmother had to have grease to make soap out of, so she saved all the deer and turkey bones and put up an ash hopper, filled it with ashes, poured water on it and dripped lye to make soap. People couldn't go to the store and buy a can of lye to make a pot of soap in those days. In fact, with the exception of a few, they did not know there was such a thing as concentrated lye.

I was very small at the time of the Civil War and do not remember much about it, but I remember well when it was over, for Uncle Spence Wood was in the war, and when it was over we heard he was coming home. We were so glad that he had gone through the war without a scratch, that all who could went to meet him. He fought in several big battles and said the Yankees, as the Northern men were called in those days, came near cutting him off from his command in one battle. He was riding an old sorrel straight-backed horse and said he just turned old "Straightie" loose and out-ran them, and got back to his command safely. I remember the old horse he called "Straightie" as well now as the day I saw Uncle Spence come riding him home from the war. Uncle Spence was the only one of father's brothers who was in the Civil war. The rest of them were on duty guarding the frontier against the Indians. My father belonged to the Minute Men. They served as rangers to scout after the Indians, although they did not have to scout but ten days each month. If the Indians made a raid they were supposed to he ready to go at a moment's notice. That is why they were called Minute Men. Sometimes my father would be gone for three weeks at a time, and we had no one to look to for protection but my dear mother. We felt safe as long as she lived, for she could shoot a gun as good as any man. Father often said that she could beat him shooting a sixshooter. I've seen her get her gun and get out after a bunch of turkeys that came close to the house when father was gone. I know she was one of the best women that ever lived. I was only eleven years old when she died. We were living in San Saba at the time of her death. She left seven children, one girl and six boys. Our sister was the oldest child, and I was the oldest boy. Sister has been dead for several years, and I have been an invalid for over thirty-two years, not being able to walk a step without the use of crutches. This was caused by being stuck in the right side of my neck with a knife by my brother-in-law, J. A. Thompson, while I was waiting on him when he had slow fever. He was either crazy or in a delirious state, and never knew anything more after he stuck the knife in me. That was September 23rd, 1894, and he died two days later.

My mother was like most of the other women in those days. She had to card, spin, weave, make clothes for the family, knit sox and other similar duties. People didn't buy everything they wore then. They did not wear silk like most of the women and girls do these days, but wore good, substantial clothes that were home made. I don't know how many pretty blankets and coverlets my mother made herself, but she had plenty to keep her family warm in cold weather, and plenty when company came to spend the night. If the women got a new calico dress in those days it was fine enough.

In our trouble with the Indians, I had two uncles killed. Uncle John Myers was killed somewhere out on the plains. We never knew for sure whether the Indians killed him or not, but the Indians got credit for it. Many people were killed then, and the blame was laid on the Indians. Uncle Boze Wood was killed on Richland Creek and Uncle Henry Wood was out north of Richland Creek at what was known as Cottonwood Pond. He was hunting when the Indians got after him and they had a running fight. Uncle Boze was shot, but got home before he died. A short while before he was killed, he and his wife were sleeping out on their porch and had two horses tied right close by so they could keep watch and try to keep the Indians from stealing them. Some time in the night the Indians slipped up and stole the horses without awakening them. They knew nothing about the Indians until the horses were gone. Uncle had several dogs lying around the house, but the Indians were so stealthy that they did not even disturb the dogs.

There was a man who lived two or three miles up the creek from us by the name of Jackson Brown. One day an Indian boy walked into Mr. Brown's yard, and going up to Mr. Brown, stuck out his hand and said "How!" Mr. Brown could not speak the Indian's language, and the Indian could not speak English, but a man named Jones, who lived further up the creek, could speak several Indians dialects, so he was sent for and soon came. The Indian boy told how he came to he there. He said a party of his tribe had come into that region, and ran off and left him there, and as he did not know where to go he decided to come to that ranch and make friends with the people there. In token of friendship he had left his bow and arrows hidden in the woods and when Jones requested him to bring them in he went out and got them. Next day Newt Brown took the Indian boy to San Saba, and as they came by our house they stopped and we were permitted to see the Indian. He was the first Indian I ever saw, and I think about the lousiest. His hair hung down on his back and had probably never been combed. It was covered with nits and lice. When Newt Brown reached town he had the boy's head shingled and a doctor put something on it to kill the lice. Newt bought him some clothes and dressed him up, and he did not look like the same Indian when he brought him back home. The Indian boy stayed with Mr. Brown a long time and seemed very well contented. He was still with the Browns when I left that country, but later I heard he went to San Angelo and lived with some Mexicans there.

Wiley Williams, who lived at San Saba, often staked his horse out to grass on moonlight nights in an open place, and he would hide somewhere nearby to watch for Indians. One night he saw an object approaching his horse and heard something like the grunt of a hog. He decided it was an Indian, so he cut down on it with a shotgun, and it ran off. Next morning he trailed it up and found a dead Indian.

I remember hearing my father tell of a company of rangers being camped near a settlement in which some of the rangers' families lived. Sometimes the men would go home to see how their folks were getting along. One morning while in camp they heard a turkey gobble in the direction of the settlement, and one of the men, who was going to the settlement, remarked that he would go by the turkey roost and if he killed a turkey he would bring it back to camp. After he had been gone a little while the men in camp heard a gunshot, and after waiting awhile for the ranger to return, he failing to do so, they decided that he had missed the turkey and had gone on to the settlement. The next morning they heard the turkey gobble at the same place, so another ranger, who had decided to go to see his family that morning, told his comrades that he would go by the roost and if he killed the turkey he would bring it to camp, but if he did not kill it he would go on to the settlement. After he had been gone awhile they heard a gunshot, and as he did not come back they supposed he had gone on home. The next morning the gobble of the turkey was heard again at the same place. Another of the men said he would go and kill that turkey. Within a short time they heard him shoot, and soon he came back to camp without a turkey. The supposed turkey was a big buck Indian, who had concealed himself in an old hollow stump, and he had killed the rangers who were on their way home. The third ranger discovered the Indian's ruse, and came up behind while the Indian was watching in another direction. So Mr. Indian got what the turkey would have gotten. The Indian got two scalps, but lost his own.

After my mother's death my father married a girl by the name of Warren. Her mother was A widow and lived in Burnet county. One day father and my step-mother left us oldest children at home to take care of the place while they went on a visit to Burnet county to see Grandma Warren. They were gone several days and while they were absent we heard our dogs barking one night as if they were baying something in our yard. We lived in a bottom where the timber made so much shade it was very dark in there after night. I yelled at the dogs and hissed them, and they created an awful furore. Next morning we found moscassin tracks in the yard, and signs among some plum bushes of a fierce struggle.

While we lived in San Saba county, before my mother's death, my father owned a beautiful dun mare, and one night he staked her out in the edge of town, not over 300 yards from where the courthouse now stands, and the Indians came along and led her off. We heard the dogs barking all over the town, and heard horses traveling through, but we supposed it was someone living there who had been out of town and were coming home. Next morning our mare was gone, and several more horses had been stolen that night from other parties.

A foul murder occurred in San Saba in those early days, which I will never forget. An old man came there from up north somewhere to buy a herd of cattle, as thousands of cattle were being driven "up the trail" at that time. Two young men came with him, and claimed to be waiting for the old man to buy the cattle and they were going to help drive them up the trail. My father and Dave Low owned a blacksmith shop in San Saba, and Mr. Low ran a hotel there. This old man, whose name I have forgotten, slept in a little room at the back of the shop, and took his meals at the hotel. One morning he failed to appear at the breakfast table, and when Low went to see about him he was found dead. He had been gagged and robbed. A big red handkerchief was tied over his mouth. The two young men were missing, and naturally suspicion pointed to them as being the murderers. They were caught near Lampasas and brought back to San Saba, and the sheriff decided to chain them together. He had father to make some irons to go around their necks, and when they were brought to the shop I watched father as he braded the irons onto their necks. One of the men confessed to the crime, and they were taken to another town for safe keeping. One of them succeeded in breaking jail and escaped, but the one who confessed refused to leave the jail. I do not know what sentence he received in the trial for murdering the old man.

After my father married the second time we moved back to Richland Creek, and there I began work as a cowboy. I helped Captain Riley Wood gather a herd of cattle. Most of these were wild cattle. Nearly all of the gentle cattle had been driven out of the country and the wild cattle would lay in a thicket all day and graze at night only. Uncle Riley Wood would take a small bunch of gentle cattle out in to the postoaks and hold them in an open place on moonlight nights and round in the wild cattle and bring them in to the pen. I was too small to make a hand rounding in at night, but I could help hold the herd. We gathered a big pen full, and Uncle Riley thought it would be best to stand guard around the pen to keep the cattle from breaking out. While he and Uncle Spence Wood were standing guard the first night, the cattle became frightened and stampeded, tearing down one side of the pen for some distance and making an awful noise. I was asleep in camp and when I became thoroughly awake and realized what had happened I found myself up in a tree. The cattle were finally rounded up with the loss of twenty or thirty head. We had some beef steers in that herd which must have been twelve of fifteen years old, and I believe them the largest steers I ever saw. A man did not need much money in these days to buy a herd of cattle, for they were very cheap. A big beef steer was worth about $10, and about all the money needed was enough to bear the expense of gathering them and driving to market. When the herd was ready to start up the trail the inspector would be notified and he would come and inspect the cattle, tally them, and the road brand would be put on. Then they would be ready for the long drive up the trail to Kansas. The inspector would give the trail boss a pass on his herd to show that they had been inspected, and he would also have the tally put on record in the county clerk's office, and the cowmen could go and look at this record and if they found anything in their mark and brand the owner of the herd would pay them for their stuff when he had sold the cattle, if he was an honest man. But sometimes there were dishonest men who carried herds up the trails, and didn't come back.

It was in 1870, I think, when about 75 Indians made a raid down Richland Creek and gave us a pretty bad scare. Warren Hudson lived near the headwater of the creek, and the Indians rode near his house, while he stood in his doorway and watched them. They took a pony he had staked near his house, and rode on down to where the Harkey children lived. There were twelve or thirteen of these children on the place, their parents having died, they lived there on the old homestead. When the children saw the Indians coming they all ran to the house, except one little girl, who climbed a tree and remained concealed among the branches until the Indians passed on. As they passed the house Joe Harkey got his gun and fired two or three shots at them, but the Indians rode on as if they never knew anybody had shot at them. Further down the creek they ran into about fifteen cowmen with a bunch of cattle rounded up, and had quite a battle with them. It was about a mile from our place and we could hear the firing. Soon the cowmen came dashing to our place, with Alex Hall in the lead. They told father to flee as the country was full of Indians. We went over to Uncle Spence Wood's place, and prepared for a fight. The cowmen reported that a man named Bomar had been killed by the Indians, but this proved a mistake, as Bomar came in next morning unscratched. The Indians had chased him pretty close, but he found refuge in a hole of water under a bluff, and they failed to get him. In the fighting Parson Davis was wounded with a lance, but soon recovered. It is not known how many Indians were killed. The Indians came to the Widow Lindley's house, and found nobody at home. They robbed the house and then burned it. Uncle Riley Wood was in this fight, and shot at an Indian that had a skirt on his head. He dropped the skirt on the battleground, and it was found to belong to Mrs. Lindley.

After this raid the few families living on Richland Creek decided that they had no chance against large bands of Indians, so we all moved down on the river near San Saba town. We crossed the trail where the Indians went out and saw plenty of signs of the battle they had with the cowmen.

_____________________________________

Enjoying this story?

Join our Facebook closed group here

_____________________________________

Out on that wild frontier in those days we were often frightened and alarmed. We were momentarily expecting Indian raids, and just to show how easily we were frightened I want to relate an insignificant incident as an illustration. While we lived on the San Saba river, before we moved bark to Richland Creek, there were four families living on the east side of the river. Our family lived where the road crossed going to San Saba. Pick Duncan and family was next up the river, about a quarter of a mile distant, and a little further up was Uncle Spence Wood's place. Above him lived George Barnett. Father and Uncle Spence were gone from home one night and we went to stay all night with Uncle Spence's folks. Just after dark we heard women and children screaming down at Duncan's camp, and we thought something awful had happened there. We were so sure that Indians had attacked the camp that we all ran up to George Barnett's and stayed there all night. The women sat up all night and every little noise they heard they just knew the Indians were coming. Next morning it was learned that one of Mrs. Beattie's little girls was hurt while playing in the yard, which caused all of the fuss. Mrs. Beattie was a widow, and a sister to Mrs. Duncan.

When the Indian raids became less frequent we moved back up on Richland Creek to our old home, but for several years the raids continued. My father had a good bunch of horses and the Indians kept stealing them until all were gone.

When I was old enough to drive an ox team, I became what the people called a "bull whacker." The last time I was in Austin I and a man named John Stevenson went with an ox-team each from San Saba to Austin after a load of lumber. The distance was one hundred miles, I think, and we received $1.00 per hundred for hauling It was in the winter time and we weren't feeding our oxen. We hobbled them out at night, as the range was fine and they could get plenty of grass to eat. They would hit the road just after dark and go just as far back towards home as they could get, and next morning just before daylight and sun-up, they would quit the road, go off behind a thicket, lay down, and keep so still we could not hear their bell rattle when we went in search of them. We always put a bell on one ox of each yoke. This may sound like a big yarn to anyone who never drove an ox-team, but those who have had the experience of freighting with oxen know their tricks. Before we reached Austin on this particular trip it came a big snow storm and covered the ground several inches deep. We stopped at the edge of a little town, which I think was called Bagdad, and bought feed for our oxen from a man named Oliver, and he let us sleep in his barn. We were a month on that trip.

Uncle Spence Wood and myself made a trip with an ox team to the Concho river and gathered a wagon bed full of pecans. The country was full of wild game, and we had a wonderful time, but we had to keep on the look-out for Indians all of the time. That whole region was unsettled, and we saw but few people on the trip. We carried our pecans to San Saba and sold them for four cents per pound.

When I was seventeen years old father moved to Fort McKavett to haul cord wood and prairie hay for the fort, and we remained there one summer and fall. While we were there we lived on the north side of the river in a settlement called Scabtown, and one night two government freighters were camped about a mile down the river. The Indians attempted to drive off their horses and one of the freighters shot an Indian. The redskin fell from his horse and was found lying there next morning flat on his back, dead, with his left arm across his breast, his right arm clown by his side his elbow resting on the ground anti his six-shooter in his hand, the hammer pulled back and his finger on the trigger ready to shoot. He was killed with an old rim-fire winchester. We called those old guns "yellow-leg winchesters," because the sides were brass. The ball went through that Indian's shield and through him too.

At the time we were living here Frank Jones was a guide and scout for the troops at Fort McKavett. On one occasion the soldiers went but and followed an Indian trail for a long ways, finally overtaking the redskins. Several Indians were killed and three squaws and a small Indian baby were captured, and brought back to Fort McKavett. I saw these captives when they were brought in.

Father secured the contract to cut and haul some cedar poles for a man to build a picket house and also made the boards to cover the house. We had to go over on the North Llano to get this timber, a distance of about thirty miles from Fort McKavett. When this work was finished we returned to Richland Springs.

There were bears in the McKavett country in those days, and lots of deer and turkeys, and we often enjoyed hunts. I remember a buffalo hunt we had in 1876, away up in the Colorado river country. Those who went on this hunt were Uncle George Wood, a man named Blackwell, Blufe Hamrick, Hiram Hamrick, Virgil Wood and myself, six altogether. We had three wagons, two drawn by oxen and one drawn by horses. We went out by Trickham and then up the north side of the Colorado until we got to the mouth of the Concho river. Here we saw our first bunch of buffalo, but did not kill any. We saw antelopes in great droves. A few miles above the mouth of the Concho we crossed the Colorado river and went up on the west side until we reached Oak Creek, then we crossed back to the east side to Brown's Ranch, and from there we went to old Fort Chadbourne, which had been abandoned some years before. The old buildings were partly torn down, or had fallen down. From here we went on west to Yellow Wolf creek, and struck camp. We killed all of the buffalo we wanted. We saw thousands of buffalo on the range as we were coming home.

For several years I followed the occupation of a cowboy in the San Angelo country, working for Ike Mullins, and others. Then I went over into Kimble county, where George Hamrick lived, and worked for Frank Cloudt. Later I went to work for Peter Robertson and Billie Bevans in Menard county. Their ranch was seven or eight miles below Fort McKavett, on the San Saba river. My salary was $20 per month, and I had to stay in a camp by myself on Rocky Creek. I did not have time to get lonesome during the daytime, but the nights were lonely for me.

Captain D. W. Roberts and his company of rangers were stationed at that time on the south side of the San Saba river, several miles above Menardville. I enlisted in this company at a salary of $30 per month, to serve one year in Company D. Frontier Battalion State Troops. D. W. Roberts was Captain, Lamb Sieker was first sergeant, Ed Sieker was second sergeant, Henry Ashburn and Doc Gourley were corporals, and there were twenty-five privates. The first duty assigned me was to go to San Saba with six or seven other rangers to help the officers there while district court was in session Ed Sieker was in charge of our little scout. Everything seemed to be quiet and court was conducted without any trouble. The sheriff had us to take nine prisoners to Lampasas and turn them over to the proper authorities there. I enjoyed this trip very much, as I was raised in San Saba county and found many old friends there. It was like going home on a visit.

While I was in the ranger service the stage was robbed three nights in succession down about Pegleg Station, between Menardville and Mason. Captain Roberts took me and three other members of the company and went down there to see if we could find the trail of the robbers, but without success. We started back to camp and as we were coming through the country we saw three men on horseback, each leading a pack horse, and thought perhaps they might be the robbers, so Captain Roberts stopped them and made a search, but nothing was found to implicate them and they were allowed to go on. We scouted regularly for Indians and outlaws, and were kept busy all of the time.

We made several scouts over into Kimble county on the lookout for a man who was wanted for cattle theft. I do not remember his name. He had a cow camp on a little creek called Contrary, which runs into the South Llano river just below Painted Rock. I remember the first scout I went on after this man we went from our camp on the San Saba through the woods in an attempt to slip in without anyone knowing we were in the country. We had our pack mule and supplies, with frying pan and coffee pot. I began to worry about how we were going to make bread without a pan in which to make up the dough and cook it for six or seven men. We had a sack of flour, and I was soon to learn something. Doug Coalson opened up the sack and pressed down a hole in the flour and made the dough in that sack. We cut sticks and rolled the dough around them and held them by the fire. Soon we had enough bread cooked for supper, and I think it was about the best bread I ever ate. After dark we saddled up and went over the mountain and down Contrary Creek until we got within a half mile of the wanted man's cow camp. Here we dismounted and took it afoot. When within a few hundred yards of the camp we pulled off our boots, and stealthily crept forward. As we approached some dogs began to bark and we made a rush for the camp. Ed Sieker was in the lead and ran into some vines and fell down. Tom Carson ran over him, and I ran over both Sieker and Carson. We got up as quickly as possible and charged the camp, but did not find the man we were looking for.

When my term of enlistment expired I left the ranger service. My association with the boys of Company D was pleasant and agreeable, and I will always hold in fond remembrance the friendship formed while in the service. I have not seen some of my old comrades since I quit the service. The majority of them have answered the last roll call on this earth. Several are still living, including my honored old captain, Dan W. Roberts. I went from the ranger camp to George Hamrick's in Kimble county, and then on down to the head of the Guadalupe to visit my father's family, and while there I saw all of my brothers and my only sister, also all of my half sisters and half brothers, and my stepmother. That was the last time we were all at home at the same time. My father moved to New Mexico some time afterwards and while there suffered an attack of pneumonia and died. My step-mother died January 13, 1927.

On October 2, 1881, I was married to Miss Mary Thompson, who lived on Pulliam Prong of the Nueces river, and we went to Kimble county to reside. I traded for a small piece of land on the North Llano, about a mile above the mouth of Copperas Creek, and we went to housekeeping in a tent which a man named Balcum loaned us. Later I built a log cabin on the place. After remaining here awhile we decided to sell our place and move to the Nueces Canyon. A young man named Grub Hamilton came along and offered me a good price for my land, and I sold it to him, and we moved to Edwards county in the spring of 1882. I settled on some school land near the headwater of Pulliam Prong of the Nueces River, in Edwards county, and I am still living on the place, I own two and a quarter sections of land and have it stocked with Angora goats. We had five children born to us, two girls and three boys, Belle Delia, Jim, Bunk and Dan. Belle died when she was two years old; Delia married R. T. Craig. Our youngest boy, Dan, died about six years ago.

I have had many interesting experiences on the frontier, which if published would fill a book.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

AN OLD BANK Seguin (Texas) Enterprise We note with interest that several banking institutions have laid claim to being the oldest in their respective sections of the state to-wit Cuero, Gonzales, Galveston, etc. Seguin has a bank, the history and record of which should be a credit to any section. Not only in point of age, does it excel, but its substantial basis and conservative management has been well known for many years. The present banking firm of E. Nolte & Son, then known as Edward Nolte, was a banking institution in 1870 and was doing some kind of banking business as far back as the late 40's or early 50's. The first bank was located in a building whic h was formerly a Methodist Church on the corner now occupied by the Post Office. Here a general store was run by Mr . Nolte and here a safe, possibly the first in Seguin, housed most of the local currency. History disclosed that one night this safe was looted of its entire contents, which not only contained money of Mr . Nolte's, but cash which had been left there by local people for safe keeping through the courtesy of the store. All the loss was. made good by Mr. Nolte. Later a general banking business was entered into by the store and became known as E. Nolte & Sons. For many years it was Seguin's only banking institution and in several financial panics was the only bank in the entire section which did not suspend payments to its depositors. During one of these panics, when Nolte's Bank was guaranteeing payments of other banks as well as their own depositors, and a large quantity of cash was in their vaults; that they kept special guard day and night, realizing the results if the bunk should be robbed at this time. The Notle Bank was doing business when there were few others in the state outside of Galveston, San Antonio, Gonzales, Cuero and Austin.

You have just read about 2 1/2 pages of Frontier Times Magazine. Get 20,000+ more pages on a convenient SEARCHABLE flash drive with 352 complete issues of Hunter’s FRONTIER TIMES MAGAZINE here.

‹ Back