By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

TRAGIC STORY OF INDIAN CAPTIVE, MAHALA McDONALD

[From J. Marvin Hunter’s Frontier Times Magazine, January, 1951]

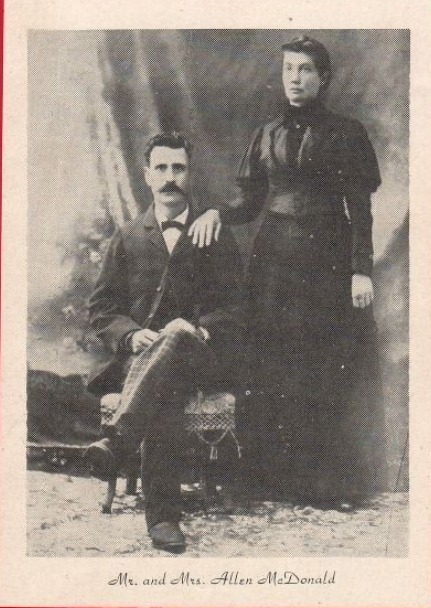

On November 23, 1931, there passed away at her home in Melvin, Texas, a daughter of Texas, whose life span of seventy years had been filled with tragedy and sorrow. She was Mrs. Mahala McDonald, who was the victim of a terrible tragedy when she was five years old, being taken captive, with her mother and younger sister, by Indians, after her father had been killed by the savages. After being kept by the Indians for several months the mother and her two little daughters were rescued from their savage captors and returned to their people. Mahala grew to womanhood and married Allen McDonald, a fine young man of the Harper section. Ten children were born to them, only three of whom are living today. Their eldest son, Irvin, was killed in a hunting accident at the age of 14, the six other children died in infancy. The living children of Allen and Mahala McDonald are H. L. McDonald of Menard, Texas; L. C. McDonald of San Angelo, Texas; and A. L. McDonald of Owens, Texas. Allen McDonald was born on Spring Creek, in Gillespie county, May 16, 1861, and died at Melvin, Texas, May 30, 1932, aged 71. His wife, Mahala McDonald, was born in Spring Creek, Gillespie county, March 5, 1861, and died November 30, 1931, aged 70. The writer knew this pioneer couple quite well, and often talked with them about their early life on the frontier. The photograph of the couple, which appears on our cover page this month, was taken a few years after they were married, and was given to us by one of Mrs. McDonald's nieces, Mrs. E. E. Spencer, of Kerrville.

A full account of the killing of the father of Mahala McDonald and the capture of her mother, herself and little sister, was furnished me some forty years ago by Leonard Passmore, who lived neighbors to the McDonalds and secured first hand details of the horrible tragedy that was enacted on the banks of the Pedernales river, where the town of Harper now stands, in August, 1865 or 1866. In order to give the account in full, I am quoting from Mr. Passmore's article:

The Tragedy of the Pedernales

There is not, perhaps, a more touching tragedy to be related of Texas frontier life than that which occurred in August, 1865 or 1866, at the head of a draw which is one of the sources of the Pedernales river, in Gillespie county, Texas, where the enterprising little town of Harper is now situated. Matthew Taylor, an old pioneer preacher, had selected this site — a beautiful pecan grove, in the edge of which was a gushing, gurgling spring — to erect a cabin , in connection with which was to be associated the fearful and heartrending destinies now shortly to be related. Before this, Matthew Taylor, with his happy little family, had been living up on the Llano river, but becoming discontented there and fearful of savage treachery, he decided to move nearer to the settlements, sparse though indeed they were — where there would be less danger of attack by Indians.

The cabin referred to was a log cabin of the frontier style. It consisted of two rooms in the main building, with a side room on the west, and an open gallery on the east, and was situated on the east side of the branch. The spring was on the west side. Near it was a great stooping walnut tree — still standing like a sturdy Roman sentinel, pointing out the spot where a family of sturdy pioneers drank the bitter dregs of frontier life. Back of the walnut, and further up the branch, was a thicket, dense as an African jungle, made up of black haw and liveoak, making an ideal place for savage ambush.

To this little cabin there came to live old Matthew Taylor and his aged wife, old Aunt Hannah, as she was familiarly called in those days; their daughter Caroline and her husband, Eli McDonald, with their two children, Mahala and Becky Jane McDonald; their son, Jim Taylor and his wife, and another son, Zed Taylor, a widower, with his three children, James, Jr., Alice and Dorcas, to be cared for by his aged mother. Thus there were together in all, an even dozen, young and old.

One day in August, somewhere about the first, old Matthew Taylor and his son, Jim, putting a yoke of oxen to a wagon, started up to the place on the Llano where they had been formerly living, to get some hay and other truck grown on the little farm they had left. Eli McDonald was left as the sole defender of the home. It was the time of light nights, and all knew that the Indians were likely to make a raid, for they generally did at that season. Usually they depredated more after horses — they had been doing so before this — and had not appeared so anxious for scalps. That they would make a raid for any purpose was only a matter of conjecture, but Mr. McDonald, like all other cautious frontiersmen, thought it best to have his weapons in readiness. His gun was a rifle that he had gotten from a man named Turkanette, who was killed during the Civil War by a party of bushwhackers. This weapon was a very trusty one, and with it Mr. McDonald believed he could withstand a considerable band of dusky marauders.

House furniture was very difficult to obtain in the early frontier homes, and while the old man and his son were gone, Eli McDonald was engaged in making a table for the time his father-in-law returned. When it was suggested that someone go to the spring to get some cold water, Gill, the wife of Jim Taylor, seized a bucket and disappeared down the path that led to the spring. The unsuspecting young woman had reached the spring, where she filled the bucket with its limpid waters and started to return, when she was pierced with an arrow from the bow of a lurking savage, who was concealed behind the big walnut near the spring. With a loud scream that reached the ears of those in the cabin, the woman, with the arrow protruding from her body, ran back through the house to the front gallery, where Mr. McDonald was at work, and gasping, fell to the floor. The blood had settled about the woman's heart and death followed instantly; in fact, she never spoke a word to the loved ones who gathered about her.

Hastily seizing his rifle, Eli McDonald ran into the house, followed by the women and children. To their surprise, they saw a large number of Indians congregating in the bottom west of the house, near where the woman had been shot. There must have been fifteen or more, and it was evident that they were preparing for an attack, though by gestures they pretended to be friendly. Seeing this, and knowing defense to be hopeless against such odds, the women prevailed on Mr. McDonald not to shoot. Coming nearer, the savages held out their hands, but the white man, knowing the treachery that lies concealed in a red man's nature, refused to accept their pretended proposals of peace. Seeing McDonald wavering, the savages, uttering a shrill warhoop, made a desperate charge. McDonald fired and reloaded. Soon his ammunition was exhausted, but his brave wife, according to her own statement, seized the bullet moulds, went to the fire and began running bullets for the rifle. The fight continued for quite an interval, but whether any of the Indians were killed was never learned, it being a custom of the savages to remove the bodies of all their slain immediately after they fell. This frontiersman, being a good marksman, however, there is little doubt but that his trusty rifle did deadly execution. But however that may have been, strength must give way to disparity of numbers, and the cruel foe was soon around the brave defender and he was being crowded too much to have time to reload. Under these circumstances, one stealthy old Kiowa — for of this tribe they afterwards proved to be — coming up in the rear, ran his lance through the white man's body, and the brave pioneer, gasping, fell to the ground.

The old lady, Aunt Hannah, afterwards said that as soon as Eli McDonald fell the savages grabbed her by the hands and led her around over the yard. They finally released their savage grip and the frightened woman hastily ran into the thicket of black haw, went on up the hollow till she reached a cave in a little bluff, where she lay concealed until nightfall. The others, consisting of Eli McDonald's wife, Caroline; Jim Taylor's children, Alice, a girl of about twelve years, Jimmie, a boy of about ten, and Dorcas, about three; Eli McDonald's children, Mahala, a little girl five years of age, and Becky Jane, about three, were taken captive. The Indians also took all the quilts and blankets in the house, and other things that suited their savage fancy.

When old Matthew Taylor returned from his journey the next day, he beheld the ghastly form of the woman with an arrow protruding from her breast, and the body of Eli McDonald, deprived of his clothing, all gory from the lance wound, and scalped, lying in the yard some distance from the house. Entering the cabin, the old man saw that it had been ransacked, and he supposed all the rest had been killed or taken captive. Hastily mounting a pony, and leaving Jim Taylor with the dead, he rode over to his son-in-law's place, about fifteen miles away, to inform him of the tragedy and to get his help in caring for the dead. This son-in-law was Monroe McDonald, a nephew of the man who was killed by the Indians. Arriving there about 3 o'clock in the afternoon, almost frantic with grief, he told with trembling voice, amid heart-rending sobs, the story of what his eyes had beheld at his ranch on the Pedernales.

_____________________________________

_____________________________________

Hastily preparing a conveyance, Monroe McDonald and his wife and an orphan child who was living with them, Clementine Hays, went with the old man back to his ranch to find conditions exactly as had been represented. Taking the trail, Monroe McDonald followed the Indians some distance, finding that they had passed over the hill where the town of Harper is now located . As Mr. McDonald proceeded on the trail, he found some of the little dresses which had been taken from the little girls by ruthless hands, and thrown aside that the helpless children might suffer the torture of being blistered by the burning rays of the summer sun. Going on back Mr. McDonald said that all the rest, beyond a doubt, had been taken away captives. Getting together such help as could be secured in a country so sparsely settled, Mr. McDonald took the corpses down to Spring Creek and buried them in a little vale on the west bank of the stream — a plot afterwards set apart as a public cemetery. After the burying, Matthew Taylor was taken to his son-in-law's, for in his feeble and bereaved condition he needed attention; and eagerly did Mr. McDonald and his wife seek to ease the old man's tears. They lived in a cabin on a little branch called Walnut, a tributary of the Pedernales.

About the second day of the old man's stay with his daughter and son-in-law, a young man rode up and said that old Aunt Hannah was down at the Doss ranch, safe in every way, with the exception of weakness from fright and travel. In a few days, the old woman was brought over, riding the entire distance of fifteen miles or more on horseback. She related the story of her escape as follows:

"The Indians, after leading me around the yard awhile, released their cruel grip on my hands and went into the house where the others had gathered. Taking advantage of this, I hastily passed out of the yard, passing right by the mangled body of Eli McDonald, and as I passed I saw him gasp for breath. Getting into the brush, I wended my way to a little cave, where I lay concealed until the sun went down. I then started for Monroe McDonald's, but got lost and wandered around all night. I was barefooted and my feet were so badly cut by rocks that they were bleeding, and my legs were lacerated by briars and cactus. I was almost famished for water. At last I reached the Stark ranch on Squaw Creek, but changed my course and reached the Ross ranch just at daybreak. Mr. Nixon immediately sent a runner to tell of my safety."

Mrs. Eli McDonald and the children were held in captivity for nine months before being released by the Kiowas. Their release was brought about in the following manner: In Mason county, some time before, the Indians had killed a Mrs. Todd and taken her daughter into captivity . A brother of the captive girl went in quest of his sister and happened into the reservation at Fort Sill, where Mrs. Caroline McDonald and the five children taken captive with her were being held. Mrs. McDonald said she was delighted to see a white man and desired very much to speak to him, but was refused this privilege. She, however, gave some sign, and young Mr. Todd, after coming back to Texas, reported that he saw some white captives among the Indians, and from the description given, relatives here believed them to be the captives of the ill-fated settlement at the head of the Pedernales. Afterwards a man selling flour dropped into the reservation and Mrs. McDonald managed to speak a few words with him, and he promised to see that she was released. The fact was reported to the government officials, and also to old Matthew Taylor, and the captives were redeemed and returned to their people. Young Todd, through whose efforts in connection with those of other men, resulted in the return of the captives to their appreciative people, was afterwards killed by falling from a bluff on the Llano river while robbing a bee cave. His untimely death was much lamented by the relatives and friends of Caroline McDonald. The beautiful sister the young man was searching for at the time he saw the other captives was never heard of, no doubt dying a victim to savage cruelty.

Mrs. McDonald, after her release, did not seem inclined to talk of the tortures received at the hands of her cruel captors, but did relate some things to her most intimate friends and relatives, of which the following is about the substance:

"The Indians took us out on the hill where another body of Indians were herding a bunch of horses. They would tie the children on the horses and turn the horses loose and laugh at the children's frantic cries. Before this the children had been deprived of their clothing. They gave us raw meat to eat and because we could not eat it they laughed and muttered in their savage dialect to their heart's content. The children, like myself, had not been sufficiently starved to make a meal on such fare, but we were at last forced to it, beginning by eating a piece of raw liver. Coming to a large hole of water, probably on Little Devil's river, or the Llano, the Indians tied the children with lariats, threw them far into the water and after allowing them to almost drown, would pull them to the shore, and make sport of their childish fright, and the groans that escaped my lips. These and other tortures too numerous to mention came near breaking my heart and little hopes were entertained by me of a restoration to my people. It seemed that this passion of crime increased as the days passed by, and many times I would think of my dear old mother, the frantic look upon her face when last I saw her; and I would wonder how my father felt on his return. Constantly I could see the ghastly picture of my husband, lying nude in the scorching sun, a large gash in his body and his head gory from being scalped. When the cruel captors of myself and little ones had reason to believe we were lamenting over my husband, they would take his scalp from the girdle from which it was hanging to shake it with cruel hilarity in our presence. In traveling, myself and children would become almost famished for water, with the children's cries and pleadings for just one drop were pitiful, indeed. Our thirst was greatly increased by the feverish condition produced by worry and savage mistreatment. Our bodies, after being deprived of clothing, soon became a solid blister from being burned by the sun. Besides, our feet were sore from traveling, and our bodies had many wounds caused by thorny brush and briars. On arriving at the end of our journey, all the Indians in the village to which we were taken gathered around us, forming a ring. We supposed our lives had been spared at the end of our capture and along our journey in order that they might be taken at the end of the journey to satisfy the savage delight of the squaws and papooses that were left behind when the warriors were out. At one time my baby girl, little Becky Jane, became very sick, but I was not allowed to minister to her wants. I could stand at a distance and view her nude and emaciated form, and hear her pleading for a drink of water, but was not allowed to go to her. This was the most severe torture I underwent in all of my captivity. The child, however, happily recovered, and with me was afterwards purchased by the government and sent back to our home on the Pedernales. At another time a little Indian girl pushed my other child, Mahala, into the fire, causing her to be badly burned. She suffers from the effects of this wound to this day. Many other things could be related of my cruel treatment at the hands of the savages, but I do not care to tell about them.

Mrs. Caroline McDonald, after several years of widowhood, afterwards married a man by the name of Pete Hazelwood. who was killed some years after by Indians near the head of Threadgill Creek in Gillespie county. Later Mrs. McDonald married a man named Pope, and resided several years in Kerrville. She died more than forty years ago at her home between Ingram and Kerrville.

The little captive, Mahala, after growing to womanhood, married Allen McDonald. Her days were also full of trouble, she having seven children buried in a group in the cemetery before mentioned on Spring Creek. She and her husband bore their troubles patiently, and always endeavored to scatter sunshine in the pathway of others. Becky Jane married Monroe Heron, and became the mother of an intelligent set of children. Jim, the little orphan son of Zed Taylor, died some years after his release from captivity; his sister, Dorcas, married a man named Rayner, who was afterwards assassinated up on Devil's River, thus leaving this woman a widow with a large family of orphan children to be cared for. The other sister married Charlie Nabors, by whom she was deserted, and four years later she married a man named John West.

PLUS+++++

20,000+ more pages of Texas history, written by those who lived it!

*Searchable flash drive (normally $89.95)

*+ 12 hardcopy magazines! (normally $145.70)

‹ Back